Jim O'Rourke

Charles S. Abbey (October 14, 1866 – April 27, 1926)

Lewis L. Drill (May 9, 1877 – July 4, 1969)

Charles Abbey, Washington Baseball Player

Unidentified Catcher, not Farrell or McGuire of the Washington Senators

Albert Krumm, Washington Baseball Player | (January 1865 – June 15, 1937)

George Erwin Gullett Stephens (April 8, 1873 – April 1, 1946)

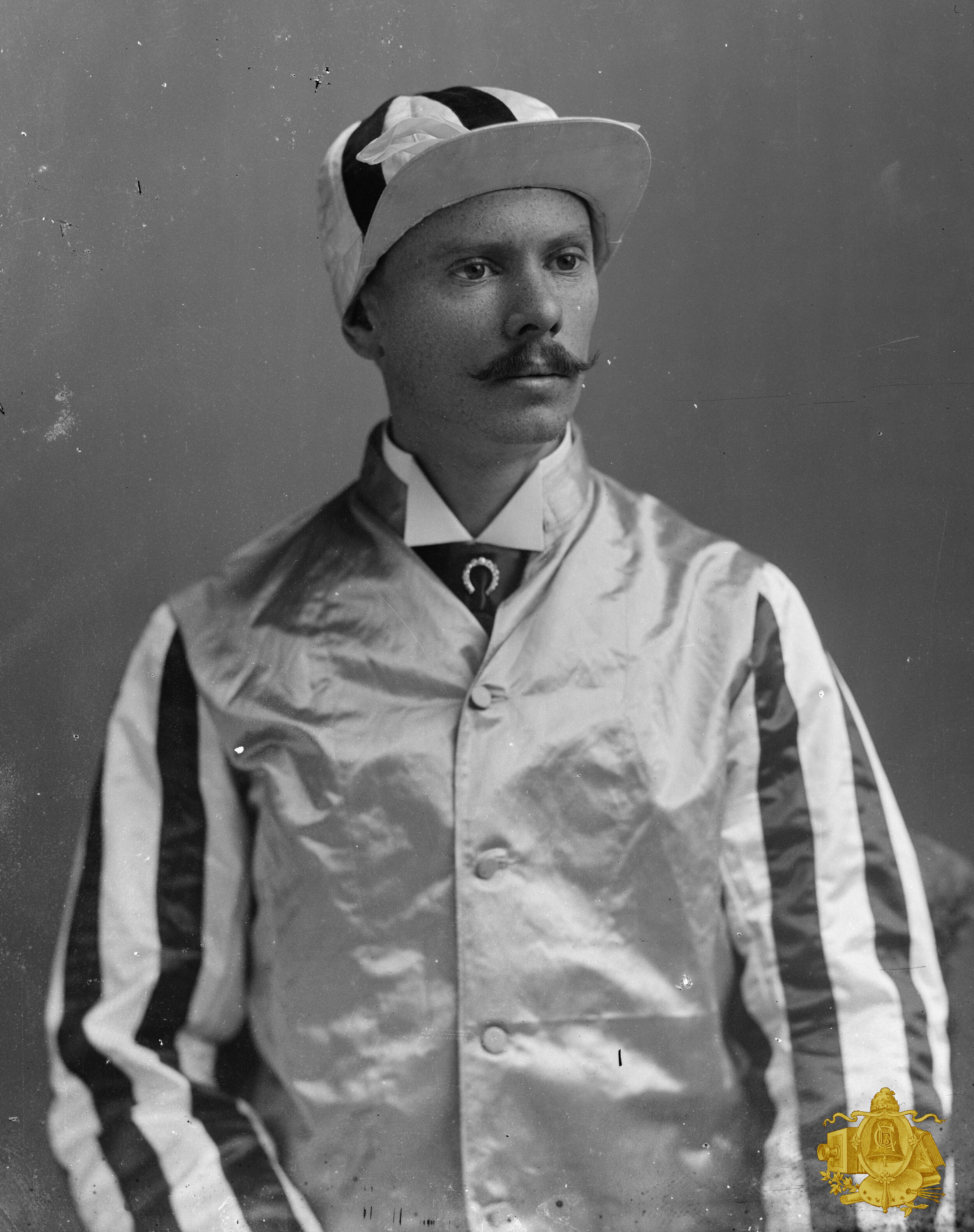

H.B. Manlove, Steeplechase Jockey, 1901

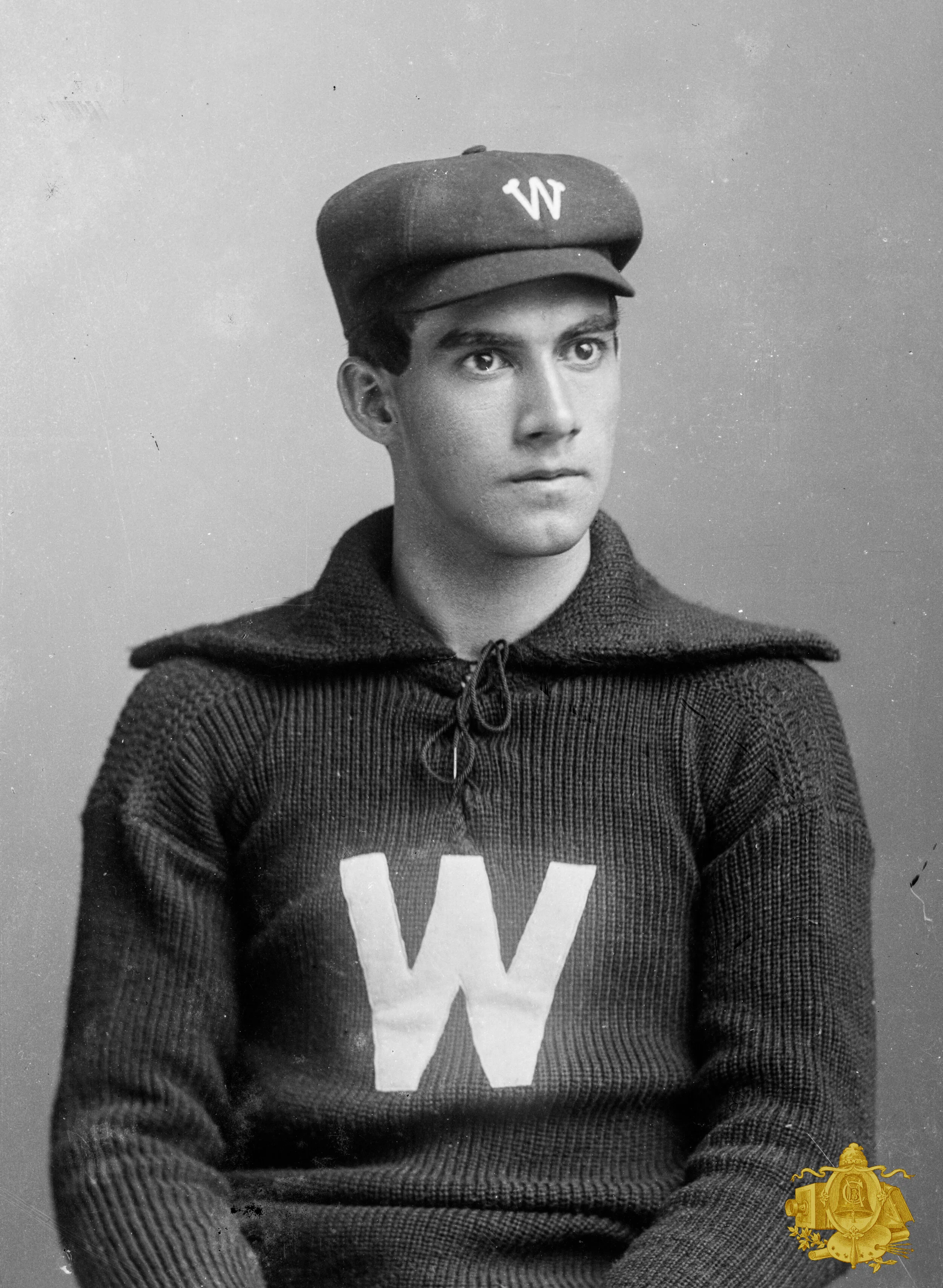

William Daniel "Willie" Merritt (January 31, 1872 – March 25, 1961) was a college football player and attorney. He was a prominent end for the North Carolina Tar Heels football team of the University of North Carolina. In 1892 Merritt was a substitute on the 1892 team which claims a Southern championship. He was selected All-Southern in 1895.

Harris Taylor "Pop" Collier (May 28, 1876 – May 4, 1935)

O'Rourke, Washington Baseball Player

Deacon McGuire

Otis Hinkley Stocksdale (Old Gray Fox) (August 7, 1871 – March 15, 1933) was an American professional baseball player who played four seasons for the Washington Senators, Boston Beaneaters and Baltimore Orioles. He was born in Arcadia, Maryland, and died in Pennsville, New Jersey at the age of 61. - Wikipedia

Daniel J. Mahoney (1864–1904) was a professional baseball player in the Major Leagues during 1892 and 1895. On February 1, 1904, Mahoney committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid in Springfield, Massachusetts. He was 39 years old

Varney Samuel "Varn" Anderson (June 18, 1866 – November 5, 1941)

Krum, Washington Baseball Player

Albert Joseph "Smiling Al" Maul (October 9, 1865 – May 3, 1958)

B.R. Cooper

W. Backus

F.M. Byrne

F. M. Byrne

A.W. Capron

Charles Gettig

G. Trentanove

Amos Rusie

W.D. Merritt

Mercer

A.C. Duganne

A.C. Duganne

M.J. Gleason

Fred Hartman

Dugdale

Win Mercer

Jim O’Rourke

Jim O’Rourke, photo by C.M. Bell

42-year-old Jim O’Rourke, his contract assigned to Washington for the 1893 season. O’Rourke assumed the post of player-manager for the Washington Senators, a former American Association franchise admitted to the National League in 1892. Appearing in all but one of the Senators’ 130 games, O’Rourke batted a creditable .287, with 95 RBIs. But his supporting crew was hapless, the team’s last place 40-89 finish prompting the release of manager O’Rourke and the end of his career in the major leagues. Including the one-year debacle in Washington, manager Jim O’Rourke posted a 246-258 (.488) record in five seasons as a major-league field leader. Far more distinguished were his accomplishments as a player: a .313 batting average over 22 seasons in the National Association, National League, and Players League, with 2,678 base hits, the most of any 19th-century big-league ballplayer not named Anson. He had also been a member of eight league champion teams.

- Society of American Baseball Research

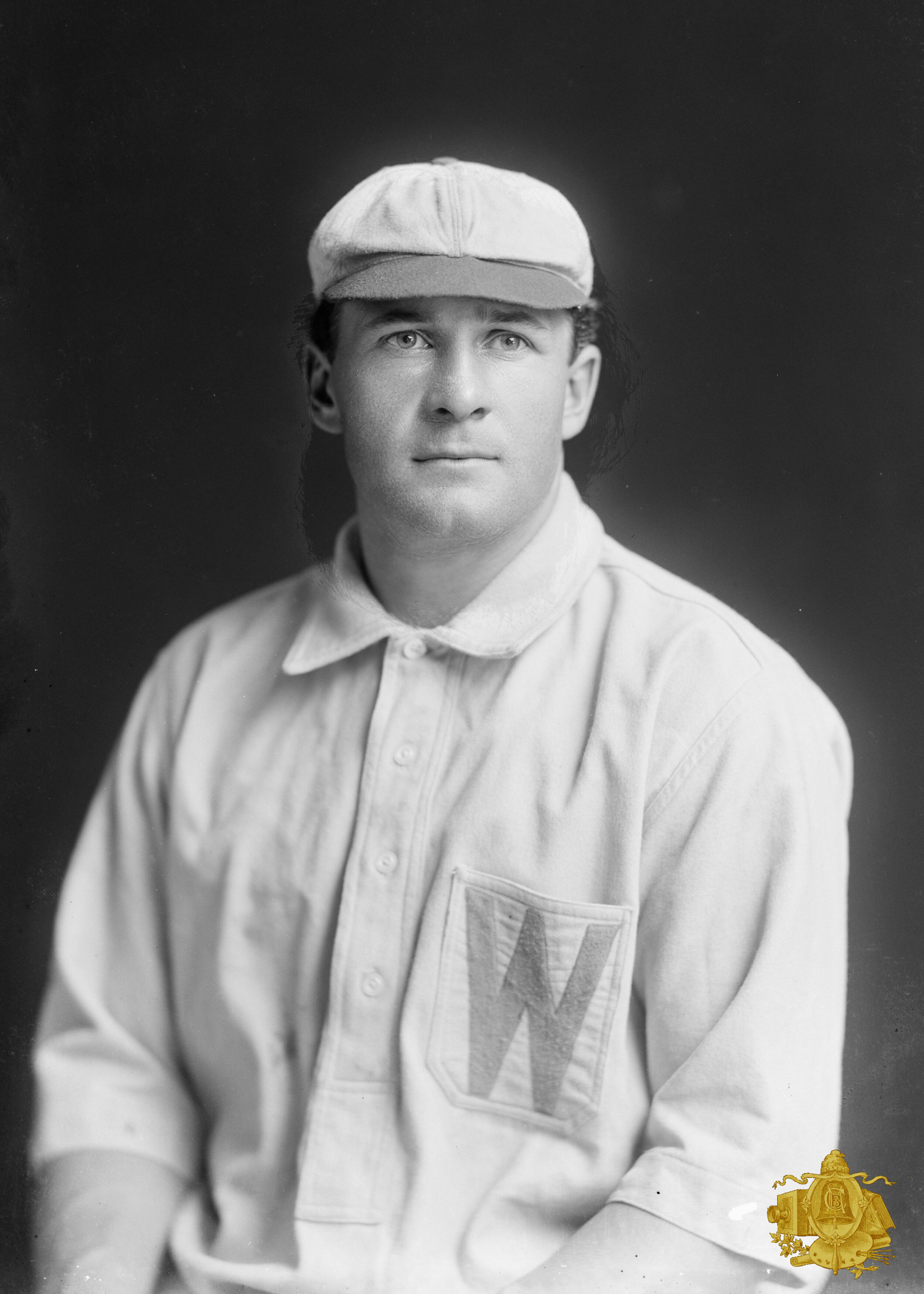

Charles Abbey, photo by C.M. Bell

Charles S. Abbey

Charles S. Abbey (October 14, 1866 – April 27, 1926) was a professional baseball player whose career spanned 11 seasons, including five seasons in Major League Baseball with the Washington Senators (1893–1897). Over his major league career, Abbey batted .281 with 307 runs, 493 hits, 67 doubles, 46 triples, 19 home runs, 280 runs batted in (RBIs) and 93 stolen bases in 452 games played. In addition to playing in the majors, Abbey also played in the minor leagues with numerous teams. Abbey primarily played the outfield position; however, he did pitch one game in the majors. Abbey batted and threw left-handed. - Wikipedia

Lewis Drill, photo by C.M. Bell

Lewis L. Drill

Lewis L. Drill (May 9, 1877 – July 4, 1969) was an American baseball player, baseball manager, and lawyer. He played professional baseball as a catcher for eight years from 1902 to 1909, including four years in Major League Baseball with the Washington Senators (1902–1904), Baltimore Orioles (1902) and Detroit Tigers (1904–1905). In 293 major league games, Drill compiled a .258 batting average and a .353 on-base percentage. He also served as the manager of the Terre Haute Hottentots in 1908. He later served as the United States Attorney for Minnesota from 1929 to 1931. - Wikipedia

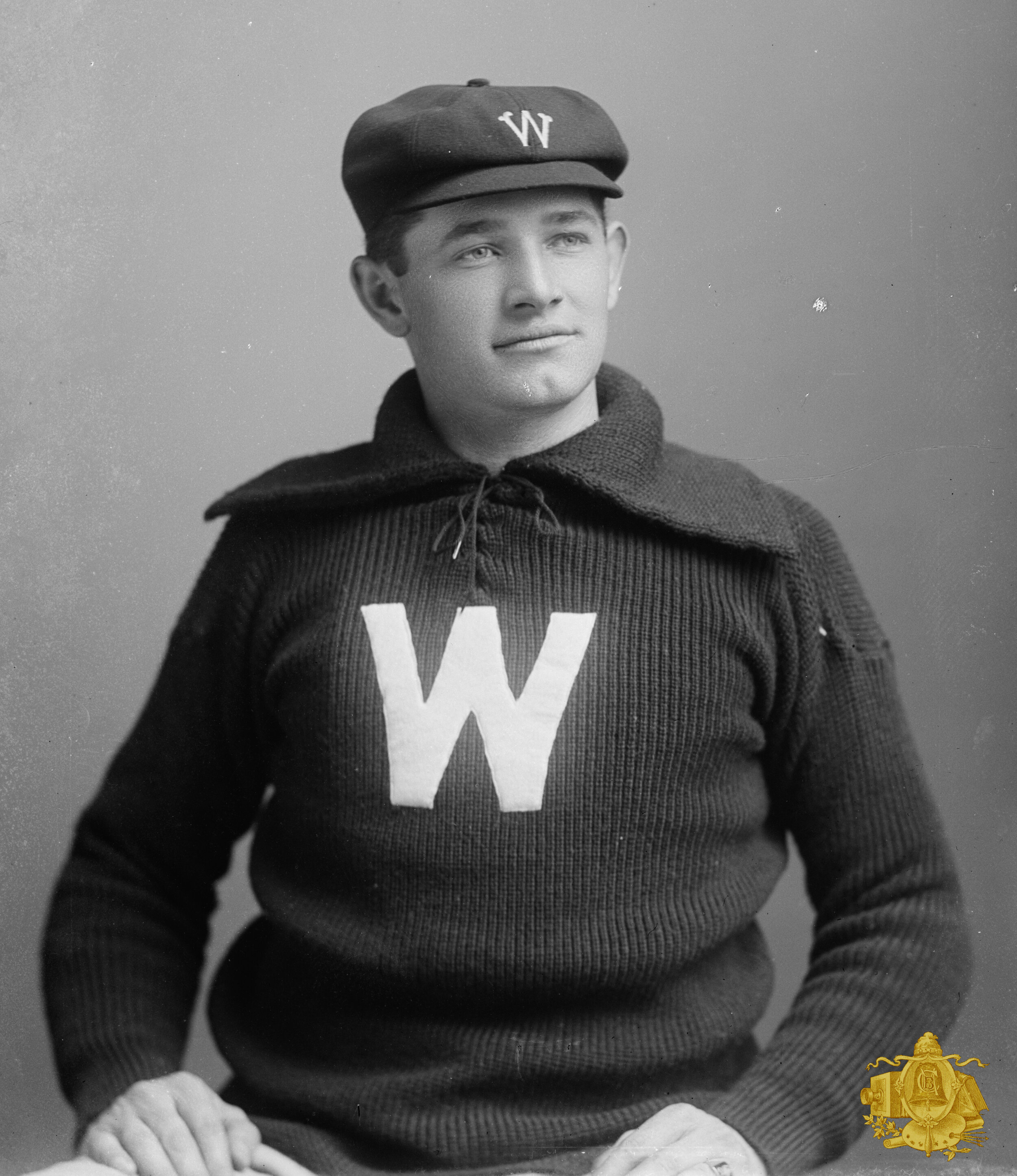

Harris Collier, photo by C.M. Bell

Harris Taylor "Pop" Collier

Harris Taylor "Pop" Collier (May 28, 1876 – May 4, 1935) was an American college football coach. He served as the head coach for Tulane (1899) and Georgia Tech (1900). Collier attended the University of Virginia, where he played on the football team and served as the team captain in 1898. - Wikipedia A native of McKenzie, Tennessee, Collier attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He played on the football team in 1895 as a guard. He also played on the baseball team as a right fielder and pitcher. Collier then attended the University of Virginia, where he studied medicine. He played on the baseball team,[6] and from 1896 to 1898, on the football team. According to a fraternity newsletter, he was considered "one of the best tackles Virginia has ever had." Collier held the position of football team captain in 1898. The yearbook, Corks and Curls ranked him as the best "all-around athlete". At Virginia, he was the vice president of the Tennessee Club. Collier then attended the Tulane University School of Medicine from which he graduated in 1900. He was a member of Sigma Nu and Theta Nu Epsilon. While a medical student,[12] Collier also coached the Tulane football team. The Olive and Blue scored no points and finished the season with a 0–6–1 record. Following his time at Tulane, Collier coached at Georgia Tech for the 1900 season, finishing 0-4-0. Collier died at the age of 58 at his home on May 4, 1935, of a cerebral hemorrhage. - Wikipedia | Photo 1895

Albert Krumm, photo by C.M. Bell

Albert Krumm

Albert Krumm, Washington Baseball Player | (January 1865 – June 15, 1937) was a Major League Baseball pitcher who played in 1889 with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys and had his single major league start on May 17th of that year. Primarily a steelworker, he had a reputation as a "troublemaker." He was in spring training with the Washington Senators in 1895 and pitched in an exhibition game with Varney Anderson but did not make the team. Krumm walked ten batters during his first game with the Alleghenys. He stayed with the team until July but never pitched again.

He was born in Pennsylvania and died in San Diego, California. - Wikipedia

Deacon McGuire, photo by C.M. Bell

Deacon McGuire

Deacon McGuire, Washington Baseball Player | In 1891, he joined the Washington Statesmen of the American Association and led all starters in batting at .303. Additionally, he led the team in doubles, triples, home runs, and RBIs. In the field, McGuire led the league in assists and runners caught stealing, but also in errors by a catcher.

The Washington team, renamed the Senators, survived the consolidation of the National League and the American Association but McGuire’s productivity regressed in 1892. McGuire batted just .232 while driving in 43 runs and leading catchers in stolen bases allowed. The Senators had started the season strong but soon dropped back to tenth place in the 12-team league. The 1893 season saw McGuire splitting time at catcher with Duke Farrell, playing 50 games behind the plate to 81 by Farrell. The careers of these two stellar catchers became inextricably linked for years to come. McGuire hit .257 and Farrell .282 for the last-place club. Farrell was traded to the New York Giants in 1894, leaving McGuire to carry the catching load. He rebounded at the plate, hitting .306 with 78 RBIs for an 11th-place Senators team. His success in 1894 only vaguely foreshadowed his historic 1895 season. - Society for American Baseball Research, Click on photo for bio. | Learn More!

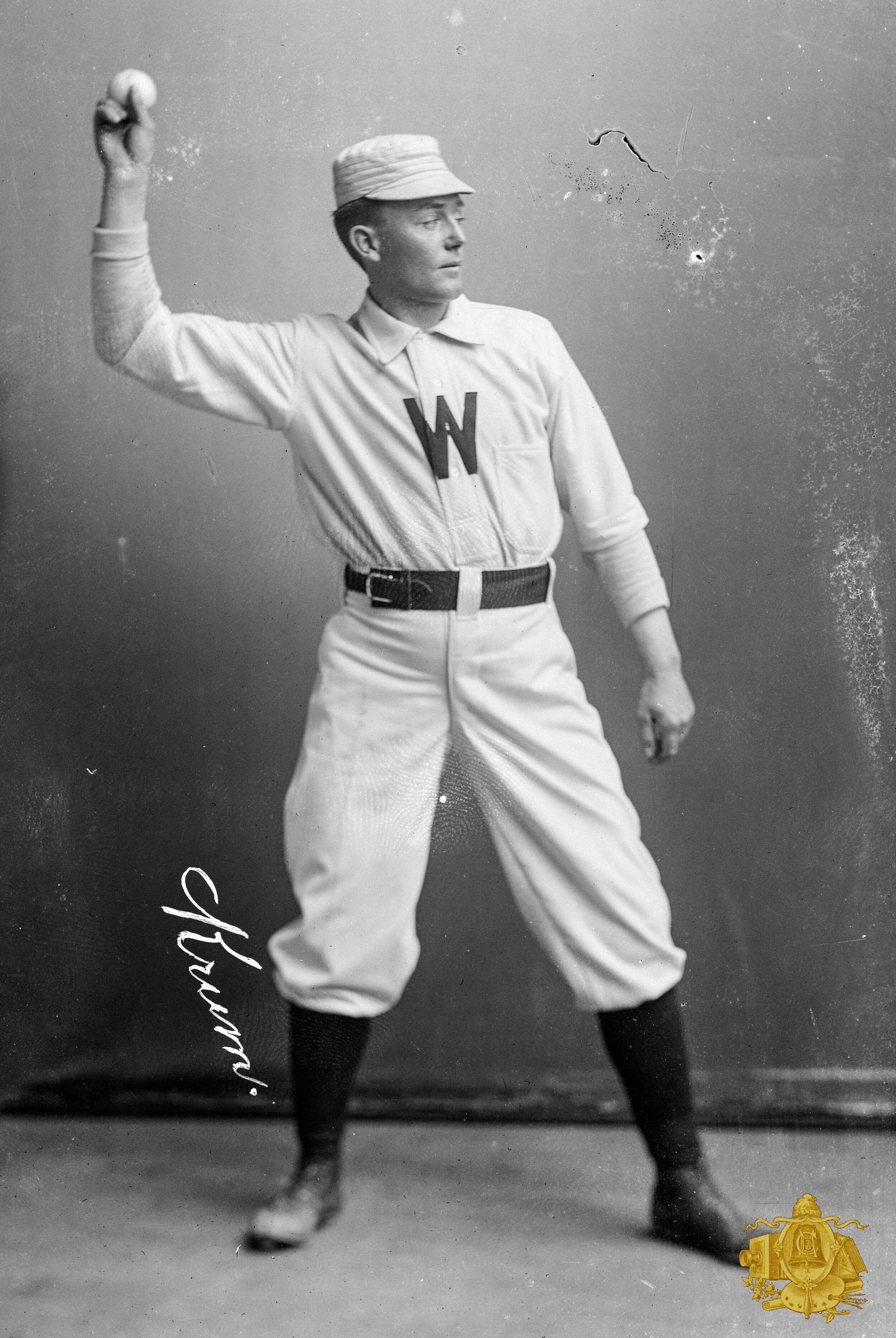

Win Mercer, photo by C.M. Bell

Win Mercer

By William Akin

In January 1903 twenty-eight year old George Barclay “Win” Mercer had already played nine years in the major leagues, won 131 games, just been given his first managerial job, and was enormously popular with fans and players. He seemed to have the world in the palm of his hand. Yet, less than two weeks into the new year he took his own life.

Rumors abounded at the time of his death with two versions emerging almost instantly. The Sporting News offered contradictory explanations of Mercer’s motives in its front page coverage. First, “there is no denying the fact that he had been gambling and apparently saw no way to make the deficit good.” According to this version, his losses included not only his own money but the funds of barnstorming major league players who were with him in California. Estimates of his shortfall ranged from $3,000 to $8,000. “Mercer’s friends admit he was a defaulter” the story contends. A second version had him leaving notes which contained the tour’s account records “which seemed to be straight.” (TSN, 1/17/1903) This version blamed his downfall on women, although the exact role women played was never made clear.

Mercer was born June 20, 1874 in Chester, West Virginia, an Ohio River town in the state’s Northern Panhandle northwest of Pittsburgh. Young George’s family moved often, first to Wheeling, West Virginia and then to the industrial city of East Liverpool, Ohio across the Ohio River from Chester.

As a teenager he pitched so well for the town’s pottery factory teams that he acquired the nickname “Winner.” This was quickly shortened to “Winnie” and then “Win.” The nickname became so much a part of him that by the time he reached the majors many sportswriters assumed “Win” was a diminutive of Winifred.

Mercer began playing professionally at age nineteen. Only 5’7″ and a thin 140 pounds, clean shaven in an era of facial hair, with dark tousled hair he looked even younger. In 1893 he went north to play in the New England League for Fall River, Massachusetts, and Dover, New Hampshire. He posted an eye popping 20-13 combined pitching record.

Gus Schmeltz, manager of Washington’s National League club, saw Mercer pitch in 1893 and purchased him for 1894. Young Mercer had the misfortune to join a bad ball club in Washington and he never experienced a good one. Washington finished no better than seventh in the six years Mercer pitched for them (1894-1899), and then the league contracted leaving DC without a team. He spent a year with the last place New York Giants before jumping to the new American League, but his two AL seasons also were spent with second division teams.

In Mercer’s rookie season, the little right-hander got off to a terrible start, but before the season ended he became Washington’s star pitcher. He lost his first nine decisions for the Nationals, but went on to post 17 wins. In addition he saved three games in relief to account for 44% of Washington’s victories. He posted a 3.85 ERA. He did experience the sophomore slump in 1895 when he slipped to 13-23 with a 4.42 ERA. A decent hitter, albeit with little power, he began to play some games at shortstop when he was not pitching.

Mercer’s best years as a pitcher came in 1896 and 1897 when he put together back-to-back twenty win seasons for a bad Washington team. In 1896 he won 25 games, including nine straight victories. The diminutive right-hander proved to be a workhorse, pitching over 300 innings, starting a league leading 45 games and pitching 38 complete games. The following season, 1898, he finished 21-20 while recording a 3.18 ERA.

Mercer quickly became a fan favorite. Only nineteen when he arrived in Washington, young and handsome with piercing dark eyes, and an outgoing personality fans found him easy to like. According to sportswriter Fred Lieb “Mercer was one of the most handsome players in the game” (Lieb, 51-52). Women, especially, liked him, and Mercer “loved the ladies” (Nash and Zullo, 129). The team’s owners liked to pitch Mercer on Tuesdays and Fridays, days designated as Ladies Days, because he attracted a crowd. According to Nash and Zullo a 1897 Ladies Day game ended in shambles when women rioted after Umpire Bill Carpenter ejected Mercer. As they described the incident: “an army of angry females poured out of the stands. They surrounded Carpenter, shoved him to the ground and ripped his clothing .Finally police brought the situation under control” (Nash and Zullo, 129).

His pitching effectiveness fell off sharply after 1897. Never a power pitcher, he got by on craft, nibbling at the corners and a nasty curve. He issued a lot of base on balls, even in his best years he walked more than he struck out. So he threw a lot of pitches. The years of overwork caught up with him in 1898. His record dropped to 12-18 on a team that lost 101 games. The next season he was even less effective winning only 7 games against 14 losses. With his pitching role reduced, he began to play more in the field, shortstop and outfield were his main positions in 1898. Although he had little power, his .321 average led the Nationals. In 1899 he became the regular third baseman, although he played every position except catcher. He hit .299 and led the club in runs, and drove in a career-best 35 runs.

The NL disbanded the woeful Nationals following the 1899 season and Mercer ended up with the New York Giants in the eight-team league. In 1899 his pitching improved to 13-17, 3.86, and he batted .294 as a utility player. Still, the Giants finished last.

When the new American League begin signing players for 1901, Mercer jumped at the opportunity to return to Washington. He signed with the new Washington Nationals for a $3,000 contract. As in 1900, he struggled on the mound for Washington (9-13, 4.56) but again batted .300 as a utility player. His return to the capital, however, lasted only one year.

Tom Loftus, brought in to manage the 1902 Nats, wasted little time in selling Mercer to Detroit. The new surrounding helped him. In 1902 Mercer appeared to regain the pitching skills which had left him after 1897. Used exclusively as a pitcher he had his best season since 1897. His 15 victories led Detroit. Moreover, his 3.04 ERA was the best of his career. That year he had the pleasure of pitching a one-hitter and a two-hitter against his former teammates. His four shutouts were second in the league to Addie Joss. Following the 1902 season, Detroit announced that Mercer would be its manager the next year at a salary of $3,800. A Washington Post writer believed the salary was “much more than any other club would care to pay him” (1/2/03). Detroit sportswriter B. F. Waight wrote approvingly of Mercer’s appointment “He is one of the nicest fellows alive” (TSN, 10/11/1902).

Mercer, along with old-time St. Louis Browns’ star Tip O’Neill, organized a three-month barnstorming tour of the west. Teams of American and National Leaguers played each other almost daily in cities between Chicago and Los Angeles. Once in California the teams split up with each playing exhibitions against local clubs. The Americans included Harry Davis, Monte Cross, Fielder Jones, Bobby Wallace, Addie Joss, and Mercer. The Nationals big names were Jake Beckley, Sam Crawford, Willie Keeler, Jesse Tannehill and Jack Chesbro.

The scheduled tour finished in San Francisco with the Americans and Nationals playing a three game series. The teams laid over in San Francisco for a few days of relaxation before heading back to Chicago. It was then, on January 13, 1903, that Mercer left the teams at the Langham Hotel and registered at the Occidental Hotel under the name of George Murray of Philadelphia. After penning several notes, he ran a tube from the gas jet into his mouth and asphyxiated himself.

Historians differ as much as did contemporary versions. Tom Deveaux believes Mercer lost in excess of $8,000 at the horse track (Deveaux, 7). On the other hand, Fred Lieb denied that Mercer had lost the players’ money. According to him Mercer “ascribed his rash act to women” (Lieb, 52). Deveaux does note that Mercer’s note warned “A word to friends: beware of women and a game of chance” (Deveaux, 7). Addie Joss became a close friend of Mercer’s on the trip and accompanied the body back to East Liverpool. According to Joss biographer Scott Longert, Joss received his share of the tour proceeds, a healthy $600. Had Mercer gambled away the players’ money Joss would have received nothing. Although this may exonerate Mercer from fraud, the reasons for his suicide remain a mystery. Deveaux’s comment that Mercer was “given to bouts of depression” (Deveaux, 7) seems an understatement. Mercer is buried in his hometown of East Liverpool, OH.

Sources

Akin, William E., “George Barclay Mercer,” in Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tieman and Mark Rucker (eds.), Baseball’s First Stars. Cleveland: SABR, 1996, p. 111.

Bulger, Bozeman, “Twenty-five Years in Sports,” Saturday Evening Post, 200 (April 28, 1928) 8.

Deveaux, Tom, The Washington Senators, 1901-1971. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001.

Gruber, John H., “Old-Time Ball Players: G.C. (Winnie) Mercer,” The Sporting News (April 1914).

Lieb, Frederick G., The Detroit Tigers. New York: G.P.Putnam, 1946.

Longert, Scott, Addie Joss: King of the Pitchers/. Cleveland: SABR, 1998.

Nash, Bruce and Zullo, Allan, “Turnstile Turnoffs: The Most Undignified Ballpark Promotions,” in The Baseball Hall of Shame. New York: Pocket Books, 1985.

The Sporting News, October 11, December 20, 27, 1902; January 10,17, 24, 1903.

“Winnie Mercer A Suicide,” New York Times, January 14, 1903.

Varney Anderson, photo by C.M. Bell

Varney Samuel "Varn" Anderson

Varney Samuel "Varn" Anderson (June 18, 1866 – November 5, 1941) was a Major League Baseball pitcher who played for the Indianapolis Hoosiers and the Washington Senators.

Anderson played professionally at least as early as 1887 for the minor league Milwaukee Brewers. He split the 1888 season between the Minneapolis Millers and St. Paul Apostles of the Western Association.

At the age of 23 years Anderson broke into the major leagues with the Indianapolis Hoosiers. In just one season, 1889, Anderson pitched just two games going 0-1 with three strikeouts with a 4.50 ERA in 12 innings pitched. In 1890 Anderson played and managed the non-affiliated Burlington Hawkeyes. For the next three seasons there is no record of Anderson playing for any major league or minor league team. He finally joined the Washington Senators where in his first year, 1894, Anderson went 0-2 with three strikeouts and a 7.07 ERA in 14 innings pitched.

The next season, 1895, Anderson was used considerably more. He was primarily a starting pitcher but did make a few relief appearances. In 29 games, 25 starts, Anderson went 9-16 with 35 strikeouts, 18 complete games and a 5.86 ERA in 2042⁄3 innings pitched. His final season with the Senators was in 1896. Anderson went 0-1 with a 13.00 ERA in only two games with nine innings pitched.

Anderson continued playing in the minors in 1897 and 1899 in Rockford, Illinois, and in 1898 for the Rock Island based in St. Joseph, Missouri. He died on November 5, 1941 (aged 75) in Rockford, Illinois. - Wikipedia

Albert Maul, photo by C.M. Bell

Albert Joseph "Smiling Al" Maul

Albert Joseph "Smiling Al" Maul (October 9, 1865 – May 3, 1958) was a pitcher over parts of 15 seasons (1884–1901) with the Philadelphia Keystones, Philadelphia Quakers/Phillies, Pittsburgh Alleghenys, Pittsburgh Burghers, Washington Senators,[1] Baltimore Orioles, Brooklyn Superbas and New York Giants. He led the National League in earned run average in 1895 while playing for Washington. For his career, he compiled an 84–80 record in 188 appearances, with a 4.43 ERA and 346 strikeouts.

In March 1893, manager Jim O’Rourke of the pitching-starved Washington Senators decided to take a chance on Maul and signed him.27 His arm evidently benefitted from the layoff. Unaffected by the elongation of the pitching distance to 60-feet, six-inches, Maul turned in yeoman, if not overly effective, work. Tossing a career-high 297 innings for a Senators club headed for a dead-last (40-89, .310) finish, Maul squeezed a team-high 12 victories (against 21 defeats) out of a 5.30 ERA/1.680 WHIP. But an open, genial demeanor and a ready smile had made friends for Maul. He quickly became a favorite with Washington teammates, fans, and sportswriters. The following spring, two other Maul character traits were in evidence: a tough-minded attitude toward salary negotiations and an aversion to spring training camp.

Maul’s second campaign in Washington near-repeated his first. He turned in a better-than-the-norm 11-15 (.423) record for another bad (45-87, .341) Senators club. But the following year, Washington, fortified by the acquisition of pitcher Win Mercer, third baseman Bill Joyce, outfielder Kip Selbach, and other first-rate talents, got off to a fast start. Maul, now featuring a pitch described like the modern slider, more than did his part, going 10-5 into July. Then, while throwing a sodden ball during a rainy July 3 game against Baltimore, something snapped in Maul’s elbow. He was finished for the season, his only consolation being a National League-leading 2.45 ERA when final stats were tabulated.

Maul was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and died there at the age of 92. At the time of his death, Maul was the last surviving participant of the Union Association. - Wikipedia

George Stephens photo by C.M. Bell

George Stephens

George Erwin Gullett Stephens (April 8, 1873 – April 1, 1946) was a college football player. He caught the first forward pass in the history of the sport. He was later a journalist who also sold insurance and real estate. University of North Carolina He was a prominent running back for the North Carolina Tar Heels football team of the University of North Carolina. He was selected third-team for an all-time Carolina football team of Dr. R. B. Lawson in 1934. Joel Whitaker selected him first-team for his all-time UNC squad. 1895, It is thought that the first forward pass in football occurred on October 26, 1895 in a game between Georgia and North Carolina when, out of desperation, the ball was thrown by the North Carolina back Joel Whitaker instead of punted. Stephens caught the ball and ran 70 yards for a touchdown. He was selected All-Southern. - Wikipedia