Sister of Providence

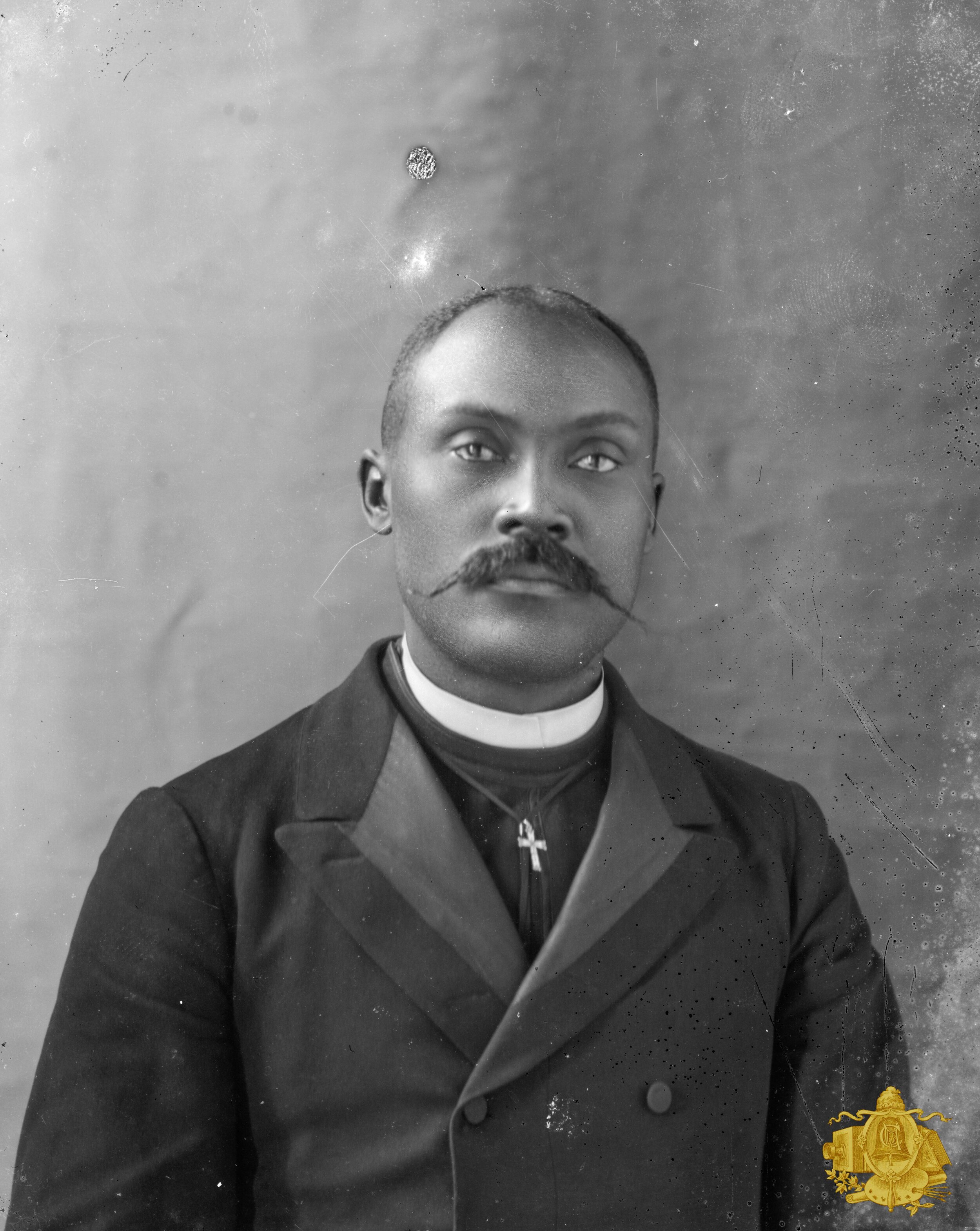

Bishop Benjamin William Arnett

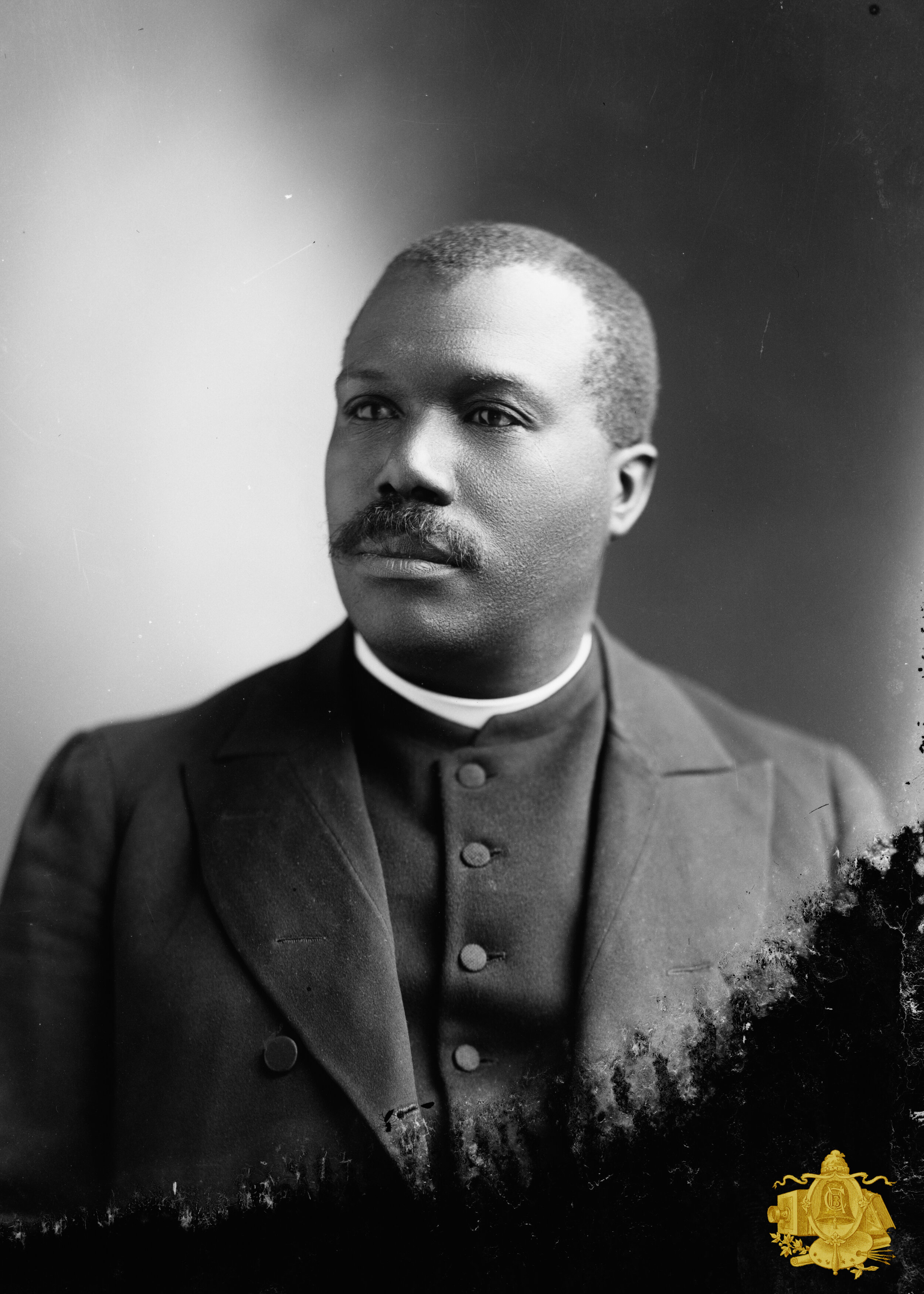

Rev. J.A. Lindsay. In May of 1896 of the North Georgia Annual Conference (Episcopal), he spoke on the life of Rev. Lawrence Thomas, and on that of Rev. Elijah Sheppard.

Bishop Lomax

J.W. Hall

Bishop Grant

Bishop C.R Harris, African Methodist Episcopal Church, Salisbury, North Carolina

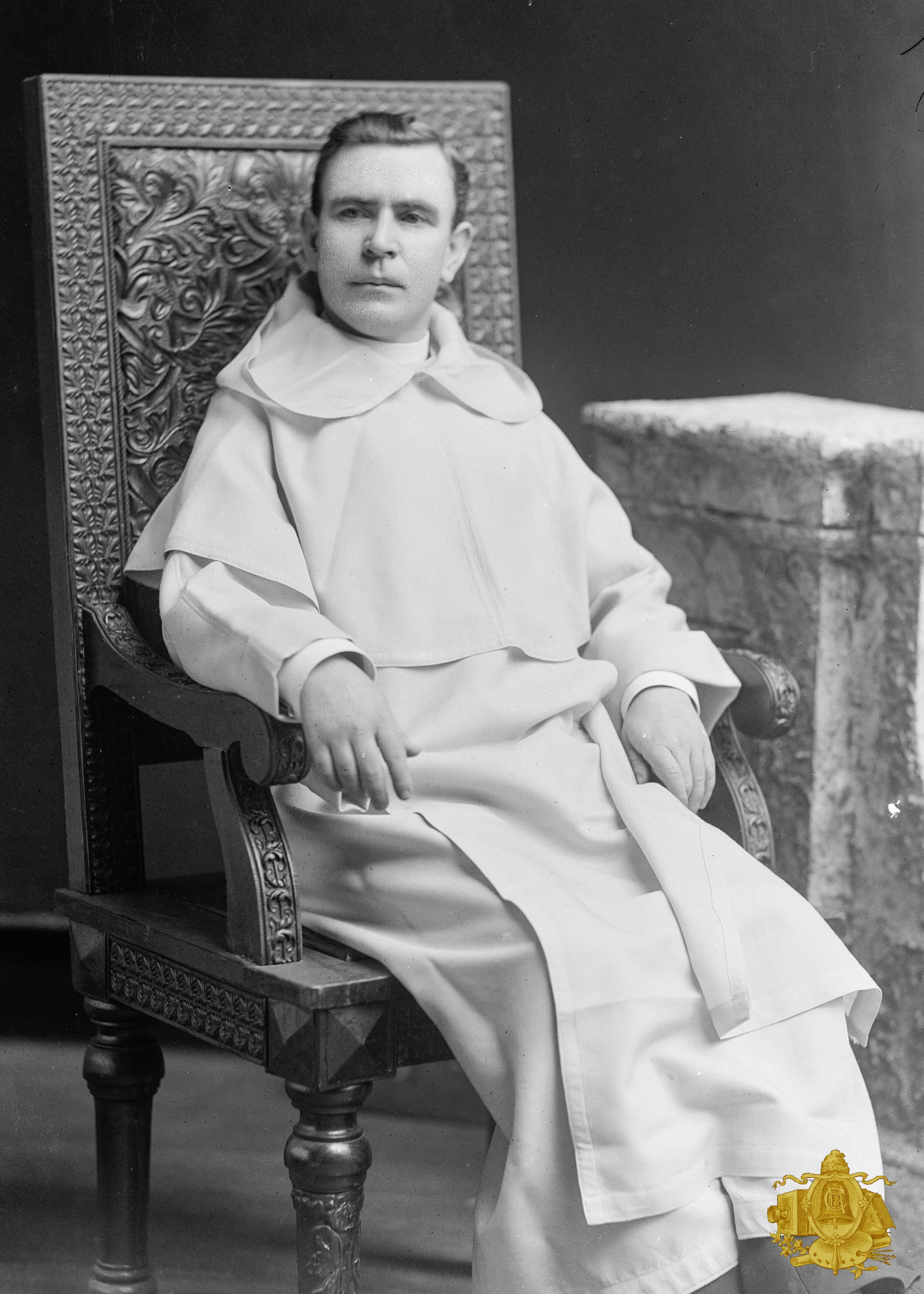

Bishop Henry Yates Satterlee.

Sister Helen

Bishop Bowman

Bishop J.W. Alstork

Sister Uriel

Rev. J.A. Myer

Bishop G.W. Clinton

Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne

Bishop Gaines

Bishop Paret

Rev. Eastman

Bishop Gaines

Unidentified Nun

Bishop Tyree

Bishop J.W. Hood

Rev. G.H.C. Bell

Bishop Randolph S. Foster

Bishop Fowler

Rev. A. Durkin

Rev. McKinna

Bishop J. W. Hood (James Walker), 1831-1918

Bishop J. W. Hood, by C.M. Bell

James Walker Hood (May 1831-30 Oct. 1918), clergyman, educator, and bishop, the son of Levi and Harriet Walker Hood, was born on the farm of Ephraim Jackson in Chester County, Pa., nine miles from Wilmington, Del. His mother, a woman of "extraordinary intelligence," was much interested in all matters affecting blacks, including a separate church for her race. His father was a Methodist minister. While living in Wilmington, Hood's parents became involved in a controversy over by white Methodists; henceforth they supported the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, established as the Methodist church for blacks.

Hood's childhood was a time of hard work, danger, and meager education. Levi Hood opposed binding any of his twelve children to an apprenticeship because he thought it similar to slavery. He did arrange verbal contracts whereby his children would work for food, clothing, and six weeks of school a year until they were sixteen. After young Hood had served a short term under a contract with Ephraim Jackson, the arrangement was ended, and he found work where he could in Philadelphia and New York. He was once kidnapped, apparently to be sold into slavery, but escaped. Although he attended school for only a few months in Pennsylvania and Delaware, his native ability enabled him to pursue general and theological studies without a teacher except for a tutor in Greek.

A religious inclination eventually led Hood into the ministry. At age eleven he experienced conversion, but questioned his beliefs until he was eighteen. At age twenty-one he mentioned to a minister his call to preach, thinking mistakenly that the clergyman would make arrangements for him. In 1856 Hood finally appeared before the New York Conference of the A.M.E. Zion church and secured a license to preach. The next year he moved to New Haven, Conn., and filled a pulpit there. In 1859 the New England Conference received him on trial and appointed him a missionary without pay to Nova Scotia. Lacking the funds to go, he worked in a New York hotel for thirteen months to become self-supporting. After being ordained deacon at Boston in September 1860, he departed for Nova Scotia. Hood landed at Halifax and walked the forty-five miles to Englewood, a mile from Bridgeton where he found a black community. Although its members were Hardshell Baptists and hostile to Methodism, Hood had gathered a congregation of eleven persons before his departure in 1863. In the interim he was ordained an elder in 1862 at Hartford. After serving in Bridgeport, Conn., for six months in late 1863, he was sent as a missionary to North Carolina where he remained for the rest of his life.

In North Carolina Hood found his major area of service. In early 1864, against the opposition of white Northern Methodists, he persuaded the black Southern Methodist congregations in New Bern and Beaufort to affiliate with the A.M.E. Zion church. When the Northern Methodists contested his conversion of these congregations to Zion, Hood was forced to appeal to the secretary of war for a ruling that permitted the blacks to align with whichever church they desired. In late 1864 he helped to found the North Carolina Conference, and over the years he aided in the establishment of numerous churches within its bounds. Hood was a pastor for three years in New Bern, two years in Fayetteville, and over three years in Charlotte. After becoming a bishop in 1872, he resided in Fayetteville until his death.

Hood became active in North Carolina politics on behalf of his people. In the fall of 1865 he presided over the first statewide political convention of blacks, which met to demand civil and political rights. In 1868 he participated in the state constitutional convention and contributed greatly to placing strong homestead and public school provisions in the constitution. From 1868 to 1871 Hood served as assistant state superintendent of public instruction, with the major duty of founding and supervising schools for blacks. Although hampered by white hostility and the lack of black teachers, he increased attendance to 49,000 students in 1871. Hood remained active in the Republican party, serving as a delegate to the national convention in 1872 and as temporary chairman of the state convention in 1876. He also served briefly as a magistrate and a deputy collector of customs and from 1868 to 1871, without pay, as assistant superintendent of the Freedman's Bureau in North Carolina.

Hood's duties as bishop took him to most states and to Europe. As an itinerant bishop, he had—by 1914—presided over several conferences annually for these total periods: New York, 27 years; New England, 24 years; Allegheny-Ohio, 6 years; Alabama, 4 years; Kentucky and New Jersey, 4 years each; California, 3 years; Philadelphia and Baltimore, 3 years; and Tennessee, 1 year. Yet most of his time he spent in the Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia conferences which he had helped to found before becoming a bishop.

One of Hood's contributions as bishop was to help establish and guide Zion Wesley Institute (later Livingstone College) in Salisbury, N.C. He presided over its board of trustees for over thirty years, educated six of his children there, and donated a good portion of his annual salary to keep it open. In 1881 Hood attended an ecumenical conference in London to help secure finances for the institute. He appointed a committee of Englishmen to direct the fund-raising, had the name of the college changed to Livingstone in honor of David Livingstone who had recently died, and provided the means for the president of Livingstone to travel in England to assist in fund-raising.

Hood's family life, although disrupted by long absences from home, centered around three marriages. In 1853 he married Hannah L. Ralph of Lancaster, Pa., who died in 1855. In 1858 he married Sophia J. Nugent of Washington, D.C., who before her death bore him seven children, four of whom survived. On 6 June 1877, he married a twenty-seven-year-old widow from Wilmington, N.C., Keziah P. McCoy, who bore him two children. Keziah Hood was a freeborn seamstress and an Episcopalian, educated in Episcopal sabbath schools and at St. Frances Academy in Baltimore.

Hood was a large man of courage, conviction, and persistence. Two of his special interests were temperance and the rights of blacks in public transportation. From 1848 to 1863 conductors of the Pennsylvania Railroad tried on numerous occasions to remove him from first-class cars, but they never succeeded. In 1857 he was put off of streetcars in New York City five times in one night, but he was not deterred. In North Carolina Hood was so insistent in demanding first-class steamer accommodations that he was never bothered after the first contest. He avoided public transportation in the Deep South because asserting his rights absorbed so much energy. Regarding his second interest, Hood participated in every temperance campaign in North Carolina.

It is remarkable that Hood, who had little formal education, should have published five books: The Negro in the Christian Pulpit (1884); One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (1895); The Plan of the Apocalypse (1900); Sermons by . . . (1908); and Sketch of the Early History of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (1914).

John L. Bell, Jr.

Source: From DICTIONARY OF NORTH CAROLINA BIOGRAPHY edited by William S. Powell. Copyright (c) 1979-1996 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

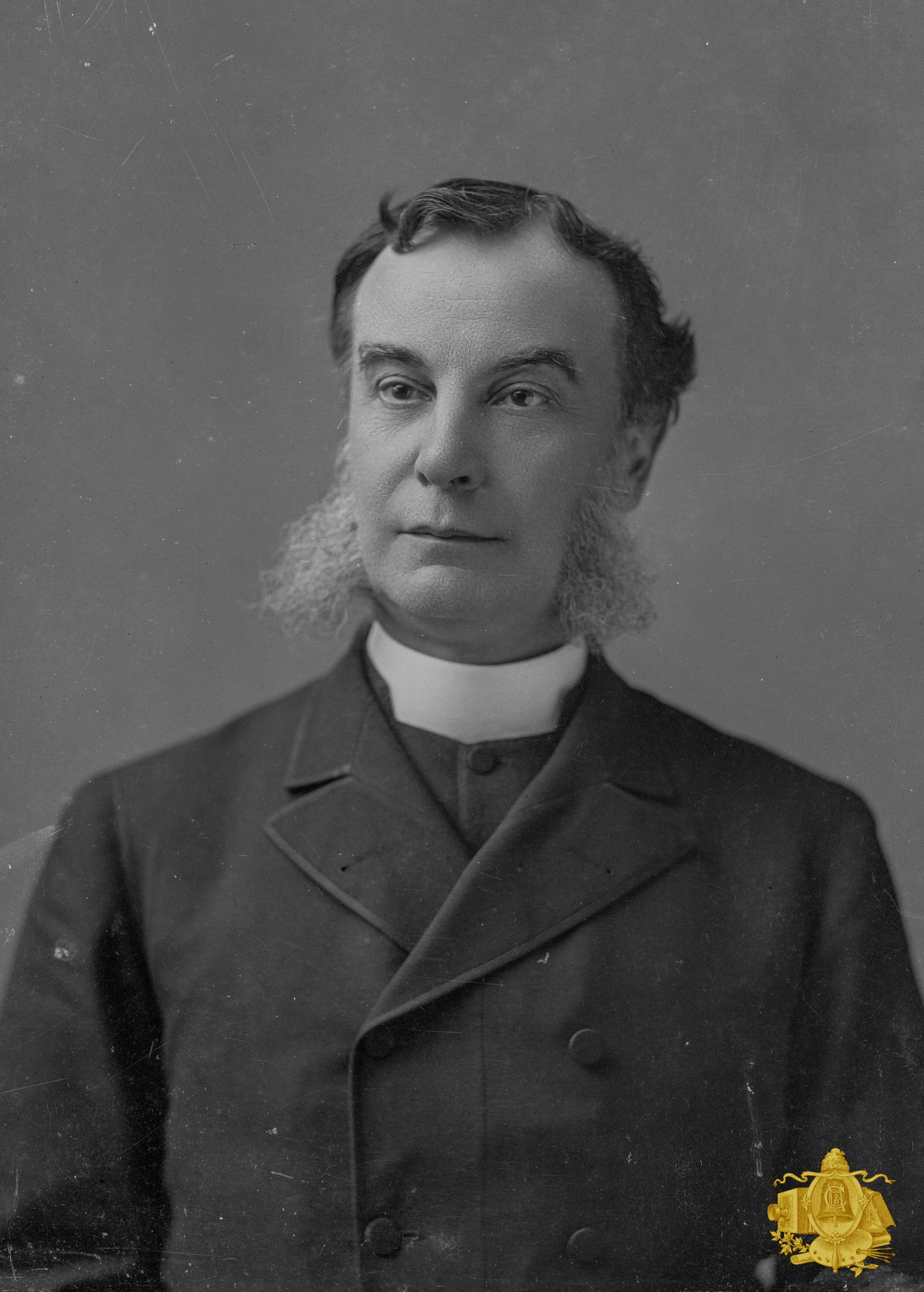

Bishop Satterlee, C.M. Bell

Bishop Henry Yates Satterlee

Bishop Henry Yates Satterlee established the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, popularly known as “Washington National Cathedral."

He was born on January 11, 1843 at the corner of Greenwich and Carlyle Streets, New York City the son of Edward Satterlee and Jane Anna Yates,[5] the daughter Henry Christopher Yates, an attorney-at-law; and for a number of years a New York State Senator and member of the Council of Appointment and Catharine, daughter of Johannes Mynderse and a grand niece of Joseph Christopher Yates, who was an American lawyer, politician. statesman, and founding trustee of Union College. He was also a descendant of Jellis Douwese Fonda, who emigrated in 1642 to the Dutch colony of New Netherland (New York).

His uncle was Charles Yates, a Brigadier-General during the American Civil War. Charles' daughter, Stella Yates (November 23, 1866 - February 2, 1929), married on June 10, 1891, in New York City, Benjamin Brewster, the son of the Rev. Joseph Brewster and Sarah Jane Bunce. He was the Episcopal Bishop of Maine and Missionary Bishop of Western Colorado.

Education

He graduated from Columbia University in 1863, and in 1866 graduated from the General Theological Seminary, New York City.

Marriage and personal life

He married on June 30, 1866, Jane Lawrence Churchill, the daughter of Timothy Gridley Churchill and Patience Lawrence. They were the parents of two children. Their son, the Rev. Churchill Satterlee, was a clergyman of the Episcopal Church. Their daughter, Constance Satterlee, married Frederick W. Rhinelander, the brother of Philip M. Rhinelander, the seventh Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania.

Ordination

On November 21, 1865, he was ordained a deacon in the Protestant Episcopal Church, and a priest on January 11, 1867. He was assistant rector of Zion Parish at Wappingers Falls, in Dutchess County, New York starting in 1865, and became its rector in 1875. He was rector of Calvary Church, New York from 1882 until 1896 when he became the Bishop of Washington, D.C. While at Calvary, he had been active in mission work to the poor in the city's Lower East Side. Satterlee gained international respect for his integrity and leadership and he also worked hard to promote the black clergy of the diocese. In 1888, he declined election as Assistant Bishop of Ohio and in 1889 declined election as Bishop of Michigan.

Consecration

On March 25, 1896 he was consecrated the first Episcopal Bishop of Washington at Calvary Church, New York City. The consecrator was to have been Bishop John Williams (1817-1899) of Connecticut, the presiding Bishop, but his fragile condition prevented him from attending. In his place, the Right Reverend Arthur Cleveland Coxe (1818-1896), Second Bishop of Western New York, presided, assisted by the Right Reverend Henry Codman Potter (1835-1908), Seventh Bishop of New York. Henry Yates Satterlee was the first Episcopal Bishop of Washington, serving from 1896 to 1908. He established the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, popularly known as Washington National Cathedral. He was responsible for acquiring its land atop Mt. Saint Alban in Northwest Washington and overseeing its construction in the 14th century English Gothic style, envisioning the role of the cathedral in state and world affairs.

Honors awarded

He received an honorary degree of D.D. from Union College in 1882 and from Princeton University in 1896; and that of LL.D from Columbia University in 1897.

Death

He died on February 22, 1908 in Washington, D.C. He is buried in the Bethlehem Chapel of Washington National Cathedral." - WIKIPEDIA

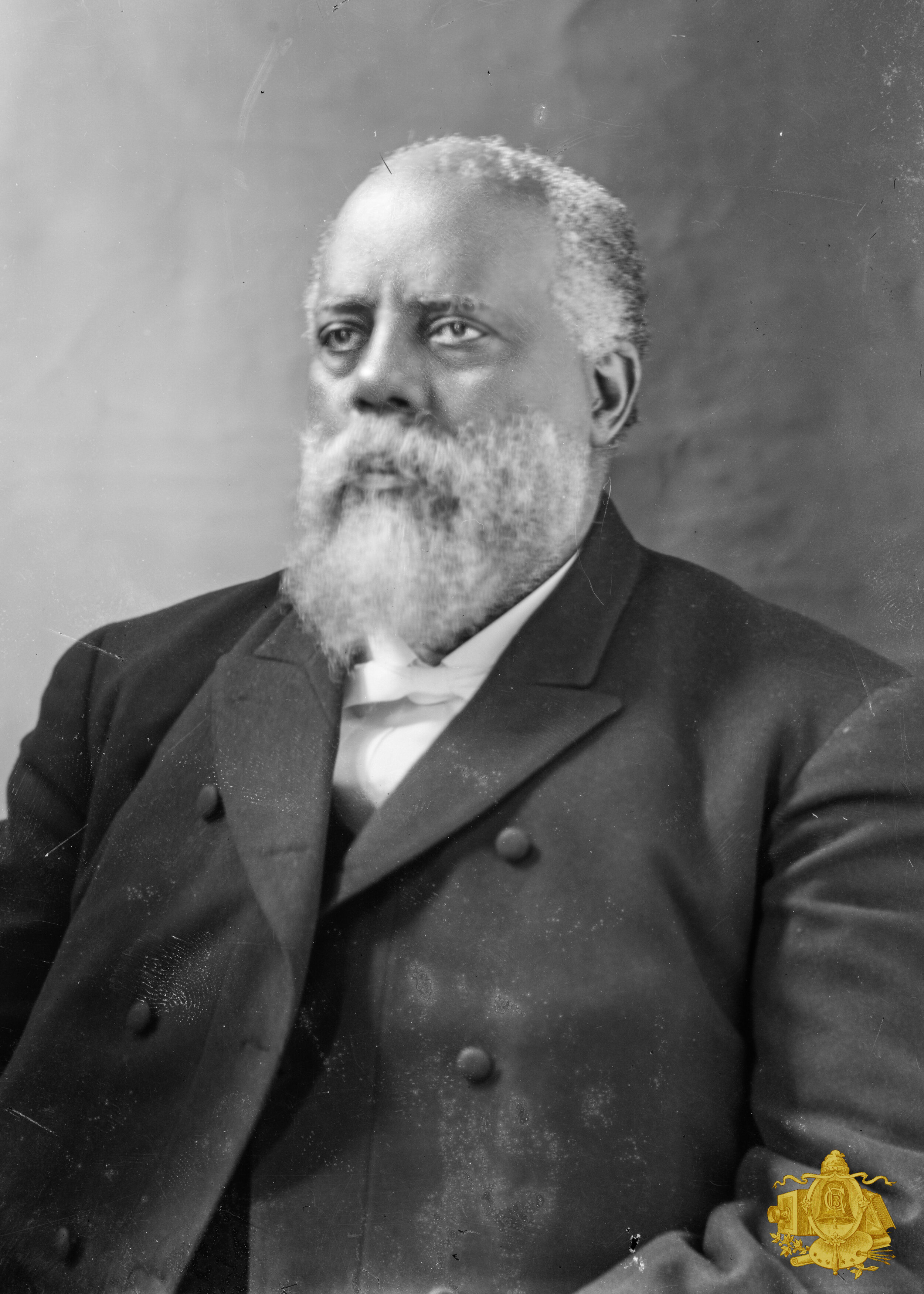

Bishop Grant

"KANSAS CITY, KANSAS, JANUARY 23, 1911 - "Bishop Abraham Grant ex-slave, educator and head of the African Methodist Church in all states west of the Mississippi River, died yesterday at his home at 533 Washington Boulevard, Kansas City, Kansas., After an illness for two months. He was 64 years old and had been Bishop of this district for 23 years.

At the time of his death he was also director of the Booker T Washington Institute for Negroes at Tuskegee Alabama director of Western University for Negroes at quindaro, Kansas and was one of the trustees have the million dollar fund left by Miss James of Philadelphia the education of negroes. President Taft, Booker T Washington, Andrew Carnegie and JH Dillard of New Orleans where other members of the Board of Trustees.

Bishop was an ex-slave and was born in an oxcart on the way from Jacksonville to Lake City Florida while his mother who had been sold was being taken home by her new master. he went by the name of his master which was Rollins until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Lincoln. Then he took the first name of the president and the last name of one of his generals. Thus he became Abraham Grant.

After the war Grant went to Jacksonville and became head waiter at the leading hotel in that City. The Bishops and Elders of the M E Church South. They're under Tok to assist him to a position in life befitting his abilities and interested him in the study of theology. He was ordained 39 years ago and 6 years later was made a bishop.

He lived many years in San Antonio Texas before moving the headquarters of his district to Kansas City Kansas it took an active part in the alleviation of strained relations between the two races in the former state. In the course of his work he made two trips to Africa and traveled several times to Europe to study the solution of the race problem.

His wife died just eight days before him. They leave no children. The body will be taken to the Allen Chapel at 10th and Charlotte streets, Kansas City Missouri where funeral services will be held at 11 Thursday morning. Then his body and that of his wife, which is now in the receiving vault, will be taken to their former home San Antonio Texas for burial."

Bishop Benjamin William Arnett (1838–1906)

FROM: Blackpast.org

Benjamin W. Arnett was an African American administrator, minister, and politician. He was born a free man in Brownsville, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, on March 6, 1838. The grandson of Samuel and Mary Louise Arnett, he was half African American, three-eighths Scottish, one-sixteenth Native American, and one-sixteenth Irish. Near his hometown, he attended a one-room schoolhouse that was taught by his father’s brother, Ephram Arnett.

In his youth, Arnett worked as a wagon boy, a waiter, and a stevedore loading and unloading wagons on the docks. While Arnett was working on a steamboat, he suffered an ankle injury that caused a tumor and later amputation in March of 1858. He received a teacher’s certificate on December 19, 1858, and became the first and for a while the only teacher in Fayette County. For ten months during the 1864–1865 school year, he taught and served as principal in a Washington, D.C. school, afterward returning to Brownsville to teach for another two years.

Arnett joined the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) church in 1856 and nine years later received a license to preach in 1865 at the Baltimore Annual Conference in Washington, D.C. His first appointment was at Walnut Hills Church in Cincinnati in 1867. He was ordained a deacon the next year and in 1870 was ordained an elder by Bishop Daniel A. Payne in Xenia, Ohio. Arnett served some of the wealthiest and most prestigious churches in the conference, eventually as longtime pastor of Allen Temple in Cincinnati.

At the same time, Arnett became increasingly politically active. In Syracuse, New York, in 1864, he joined the National Equal Rights League led by Frederick Douglass. Two years later, he served as secretary of the League’s Washington, D.C. convention. In 1879 he became chaplain of the Ohio Legislature, in 1880 chaplain of the Republican State Convention of Ohio, and in 1896 chaplain of the National Republican Convention in St. Louis.

Arnett became the seventeenth elected bishop of the AME Church in 1888. In 1880 and again in 1884, he was elected to financial secretary of the AME Church, a position that allowed him to settle permanently in Wilberforce, the intellectual center of the church in Ohio. In 1885 the Wilberforce College faculty chose him to run for the Greene County Republican legislative nomination. He won the nomination and subsequent election, serving in the Ohio House of Representatives from 1887 to 1889. While there, he supported Wilberforce by getting a state facility on the campus.

Arnett held numerous positions during his career, including secretary of the National Equal Rights League, life member of the National Negro Business League, secretary of Bishopric Council (1889–1896), president of the A.M.E. General Board of Education (1888–1896), president of the board of trustees of Wilberforce University (1891–1896), and vice-president of the Normal and Industrial Board of Trustees, Wilberforce (1893–1896). He was also a member of the Parliament of Religions at the 1896 Chicago World’s Fair.

On May 25, 1858, Arnett married Mary Louise Gordon, and together the couple had seven children: Benjamin W. Arnett Jr. (pastor), Alonzo, Henry Y., Daniel (pastor), Anna, Alphonso, and Florence. Bishop Benjamin William Arnett died October 7, 1906, on the Wilberforce University campus. He was sixty-eight.

Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne

Bishop Payne, C.M. Bell

Daniel Alexander Payne (February 24, 1811 – November 2, 1893) was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.), Payne stressed education and preparation of ministers and introduced more order in the church, becoming its sixth bishop and serving for more than four decades (1852–1893) as well as becoming one of the founders of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. In 1863 the AME Church bought the college and chose Payne to lead it; he became the first African-American president of a college in the United States and served in that position until 1877.

By quickly organizing AME missionary support of freedmen in the South after the Civil War, Payne gained 250,000 new members for the AME Church during the Reconstruction era. Based first in Charleston, he and his missionaries founded AME congregations in the South down the East Coast to Florida and west to Texas. In 1891 Payne wrote the first history of the AME Church, a few years after publishing his memoir.

Early life and education

Daniel Payne was born free in Charleston, South Carolina, on February 24, 1811, of African, European and Native American descent. Daniel stated "as far as memory serves me my mother was of light-brown complexion, of middle stature and delicate frame. She told me that her grandmother was of the tribe of Indians known in the early history of the Carolinas as the Catawba Indians." He also stated that he descended from the Goings family, who were a well known free colored/Native American family. His father was one of six brothers who served in the Revolutionary War and his paternal grandfather was an Englishmen. His parents London and Martha Payne were part of the "Brown Elite" of free blacks in the city. Both died before he reached maturity. While his great-aunt assumed Daniel's care, the Minors' Moralist Society assisted his early education.[3] Payne was raised in the Methodist Church like his parents. He also studied at home, teaching himself mathematics, physical science, and classical languages. In 1829, at the age of 18, he opened his first school.

After the Nat Turner Rebellion of 1831, South Carolina and other southern states passed legislation restricting the rights of free people of color and slaves. They enacted a law on April 1, 1835, which made teaching literacy to free people of color and slaves illegal and subject to fines and imprisonment. With the passage of this law, Payne had to close his school. In May 1835, Payne sailed from Charleston to Philadelphia in search of further education. Declining the Methodists' offer, which was contingent on his going on a mission to Liberia, established as a colony for free blacks from the United States, Payne studied at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania. Payne never worked as a Lutheran priest. One source claims he had to drop out of school because of problems with his eyesight. Another source claimed no congregation called him and the Lutheran Church told him to work through the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Marriage and family

Payne married in 1847, but his wife died during the first year of marriage from complications of childbirth. In 1854, he married again, to Eliza Clark of Cincinnati.

Career in AME Church

By 1840, Payne started another school. He joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in 1842. He agreed with the founder, Richard Allen, that a visible and independent black denomination was a strong argument against slavery and racism. Payne always worked to improve the position of blacks within the United States; he opposed calls for their emigration to Liberia or other parts of Africa, as urged by the American Colonization Society and supported by some free blacks.

Payne worked to improve education for AME ministers, recommending a wide variety of classes, including grammar, geography, literature and other academic subjects, so they could effectively lead the people. In the ensuing decades' debates about "order and emotionalism" in the African Methodist Church, he sided consistently with order. The AME's first task was "to improve the ministry; the second to improve the people".[8] At a denominational meeting in Baltimore in 1842, Payne recommended a full program of study for ministers, to include English grammar, geography, arithmetic, ancient history, modern history, ecclesiastical history, and theology. At the 1844 AME General Conference, he called for a "regular course of study for prospective ordinees", in the belief they would lift up their parishioners. In 1845 Payne established a short-lived AME seminary, and succeeded in gradually raising the educational preparation required for ministers.

Payne also directed reforms at the style of music, introducing trained choirs and instrumental music to church practice. He supported the requirement that ministers be literate. Payne continued throughout his career to build the institution of the church, establishing literary and historic societies and encouraging order. At times he came into conflict with those who wanted to ensure that ordinary people could advance in the church. Especially after expansion of the church in the South, where different styles of worship had prevailed, there were continuing tensions about the direction of the denomination.

Bishop and college president

In 1848, Bishop William Paul Quinn named Payne as the historiographer of the AME Church. In 1852, Payne was elected and consecrated the sixth bishop of the AME denomination. He served in that position for the rest of his life. Together with Lewis Woodson and two other African Americans representing the AME Church, and 18 European-American representatives of the Cincinnati Methodist Episcopal Conference, Payne served on the founding board of directors of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. Among the trustees who supported the abolitionist cause and African-American education was Salmon P. Chase, then governor of Ohio, who was appointed as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court by President Abraham Lincoln. The denominations jointly sponsored Wilberforce in 1856 to provide collegiate education to African Americans. It was the first historically black college in which African Americans were part of the founding.

Wilberforce was located at what had been a popular summer resort, called Tawawa Springs. It was patronized by people from Cincinnati, including abolitionists, as well as many white planters from the South, who often brought their mistresses of color and "natural" (illegitimate) multi-racial children with them for extended stays.

In one of the paradoxical results of slavery, by 1860 most of the college's more than 200 paying students were mixed-race offspring of wealthy southern planters, who gave their children the education in Ohio which they could not get in the South. The men were examples of white fathers who did not abandon their mixed-race children, but passed on important social capital in the form of education; they and others also provided money, property and apprenticeships.

With the Civil War, the planters withdrew their sons from the college, and the Cincinnati Methodist Conference felt it needed to use its resources to support efforts related to the war. The college had to close temporarily because of these financial difficulties. In 1863, Payne persuaded the AME Church to buy the debt and take over the college outright. Payne was selected as president, the first African-American college president in the United States. The AME had to reinvest in the college two years later, when a southern sympathizer damaged buildings by fire. Payne helped organize fundraising and rebuilding. White sympathizers gave large donations, including $10,000 donations each from founding board member Salmon P. Chase and a supporter from Pittsburgh, as well as $4200 from a white woman. The US Congress passed a $25,000 grant for the college to aid in rebuilding. Payne led the college until 1877. Payne traveled twice to Europe, where he consulted with other Methodist clergy and studied their education programs.

In April 1865, after the Civil War, Payne returned to the South for the first time in 30 years. Knowing how to build an organization, he took nine missionaries and worked with others in Charleston to establish the AME denomination. He organized missionaries, committees and teachers to bring the AME church to freedmen. A year later, the church had grown by 50,000 congregants in the South.

By the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877, AME congregations existed from Florida to Texas, and more than 250,000 new adherents had been brought into the church. While it had a northern center, the church was strongly influenced by its expansion in the South. The incorporation of many congregants with different practices and traditions of worship and music styles helped shape the national church. It began to reflect more of the African-American culture of the South.

In 1881, he founded the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, a club which invited speakers to present on topics relevant to African-American life and a part of the Lyceum movement.

Payne died on November 2, 1893, having served the AME Church for more than 50 years.

Works

1888, Recollections of Seventy Years, a memoir.

1891, The History of the A. M. E. Church, the first history of the denomination.

Citation: Daniel Payne. (2021, January 1). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Payne

Rev. J.W. Hall

Born in 1867, The Rev. J.W. Hall was a spiritual presence in the African Methodist Episcopal Church up and down the Ohio Valley in the Gilded Age. Across the decades, his sermons were heralded in Western Kentucky as he was a leader in several general conferences from 1908-1916. He married Mrs. Henrietta Hall, of Franklin, Ky., in 1896. He contributed to several Recorders and A. M. E. Review. He wrote "Plain Talk on Church Entertainment," "Paul's Thorn in the Flesh," "Divine and Human Baptism."

Bishop Randolph Sinks Foster (1820-1903)

Born on February 22, 1820, at Williamsburg, Ohio, U.S., the son of Israel Foster and Mary "Polly" Kain,[2] he attended Augusta College in Kentucky but left to become a Preacher in the Ohio Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church when he was only seventeen. He was ordained to the Traveling Ministry by Bishops Waugh and Hedding. He went on to become the Pastor of the Mulberry Street M.E. Church in New York City, where he met Daniel Drew, the financier who provided the original funding for the Drew Theological Seminary in Madison, New Jersey.

Prior to his election to the Episcopacy, Foster served in pastoral appointments and in educational work. He was President of Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, 1857-1860. He also accepted John McClintock's invitation to become Professor of Systematic Theology at Drew. After the death of Drew's first President in 1870, Foster was elected to that post, remaining there until becoming a Bishop in 1872, when he was assigned to the Cincinnati, Ohio area.

He died at Newton Centre, Massachusetts on May 1, 1903.[3][4] He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York. (WIKIPEDIA)