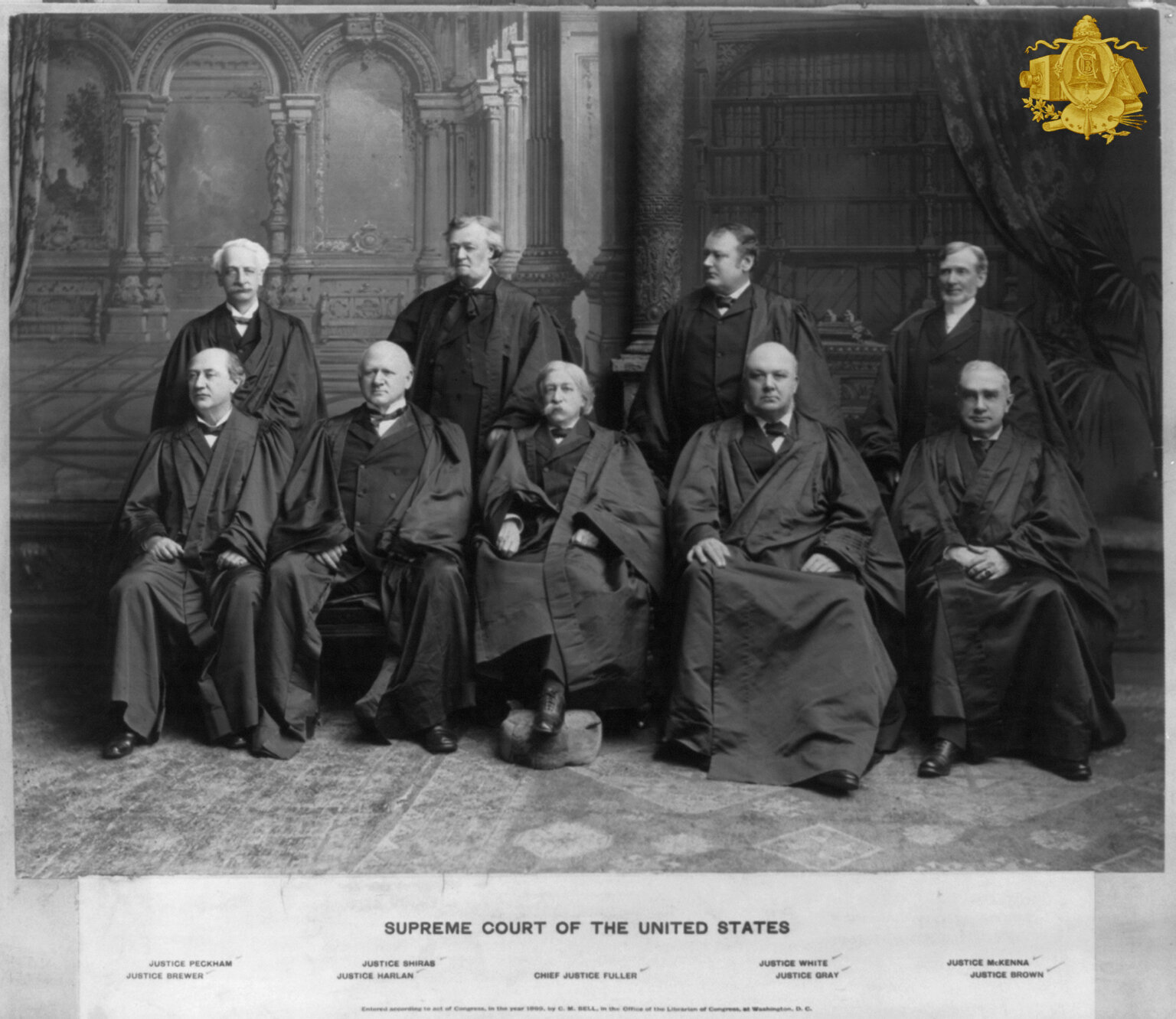

Melville Fuller, appointed by Grover Cleveland as Chief Justice in 1888, would oversee this conservative court until 1911. The Fuller Court would give wide latitude to "due process" in business considerations while narrowing its "equal protection" outlook to the citizens. Conservatives would trumpet its protection of economic liberty as liberals would lament its stranglehold on individual freedoms.

John Harlan

Justice McKenna

Justice George Shiras Jr.

Justice White

Associate Justice Henry Billings Brown

Justice White

Justice Brewer

Associate Justice Henry Billings Brown

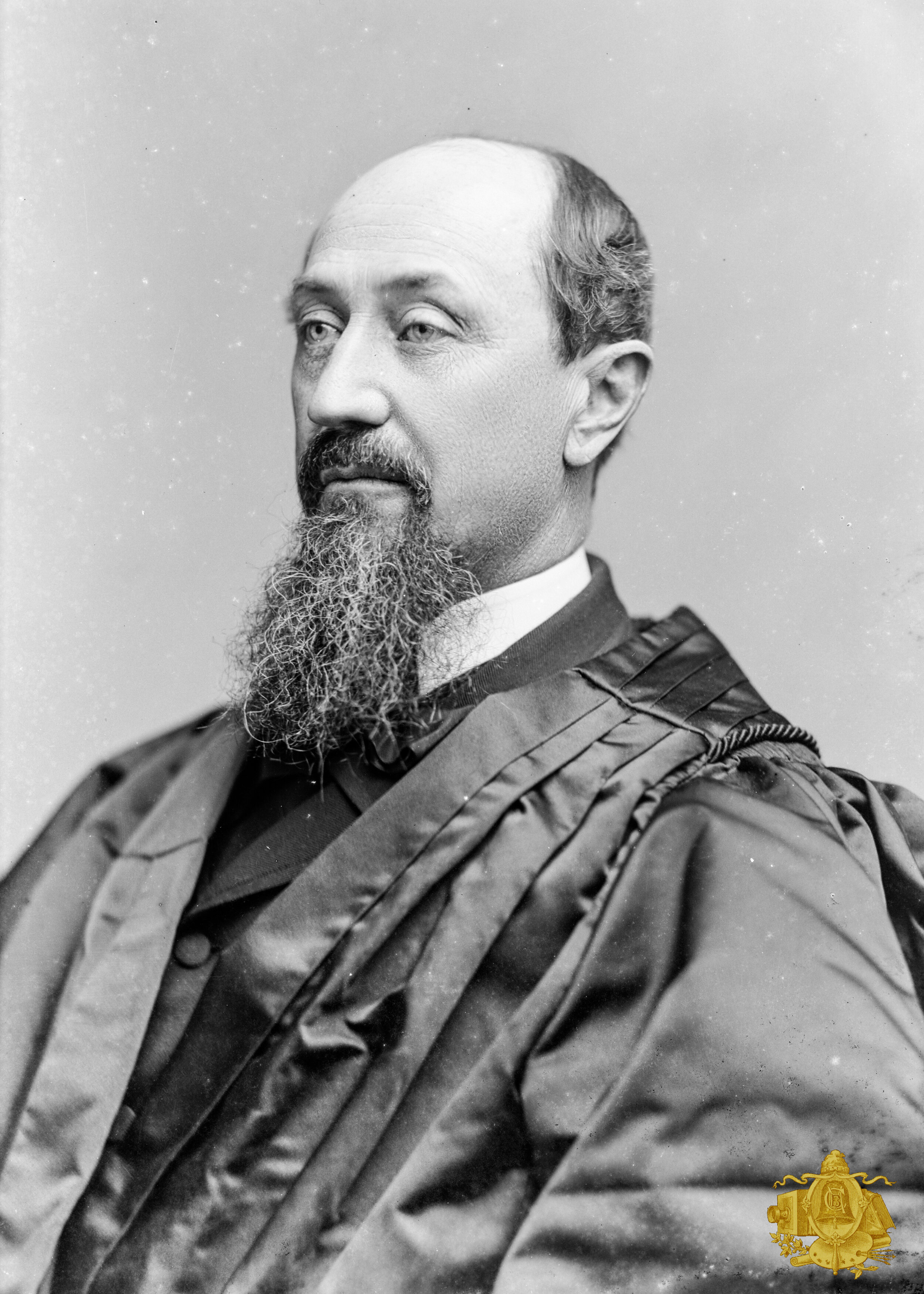

John Harlan in robes, C.M. Bell Studio

Associaite Justice John Harlan “The Great Dissenter”

Associate Justice John Harlan | A Kentuckian growing up in Henry Clay's and Abraham Lincoln's Valley of Democracy, John Harlan was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1877 - 1911. He was a member of the Know-Nothing Party, opposed to the Emancipation Proclamation, and Lincoln's 1864 re-election. Alarmed by the Jim Crow south following Reconstruction, Harlan would emerge as the lone dissenter in the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). He would be known as the "Great Dissenter" on the Fuller Court as an ardent supporter of the Reconstruction Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th) to protect the Civil Rights of African-Americans.

From THE SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE:

“He was known as “the Great Dissenter,” and he was the lone justice to dissent in one of the Supreme Court’s most notorious and damaging opinions, in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. In arguing against his colleagues’ approval of the doctrine of “separate but equal,” John Marshall Harlan delivered what would become one of the most cited dissents in the court’s history.

Then again, Harlan was remarkably out of place among his fellow justices. He was the only one to have graduated from law school. On a court packed with what one historian describes as “privileged Northerners,” Harlan was not only a former slave owner, but also a former opponent of the Reconstruction Amendments, which abolished slavery, established due process for all citizens and banned racial discrimination in voting. During a run for governor of his home state of Kentucky, Harlan had defended a Ku Klux Klan member for his alleged role in several lynchings. He acknowledged that he took the case for money and out of his friendship with the accused’s father. He also reasoned that most people in the county did not believe the accused was guilty. “Altogether my position is embarrassing politically,” he wrote at the time, “but I cannot help it.”

One other thing set Harlan apart from his colleagues on the bench: He grew up in a household with a light-skinned, blue-eyed slave who was treated much like a family member. Later, John’s wife would say she was somewhat surprised by “the close sympathy existing between the slaves and their Master or Mistress.” In fact, the slave, Robert Harlan, was believed to be John’s older half-brother. Even John’s father, James Harlan, believed that Robert was his son. Raised and educated in the same home, John and Robert remained close even after their ambitions put thousands of miles between them. Both lives were shaped by the love of their father, a lawyer and politician whom both boys loved in return. And both became extraordinarily successful in starkly separate lives.

Robert Harlan was born in 1816 at the family home in Harrodsburg, Kentucky. With no schools available for black students, he was tutored by two older half-brothers. While he was still in his teens, Robert displayed a taste for business, opening a barbershop in town and then a grocery store in nearby Lexington. He earned a fair amount of cash—enough that on September 18, 1848, he appeared at the Franklin County Courthouse with his father and a $500 bond. At the age of 32, the slave, described as “six feet high yellow big straight black hair Blue Gray eyes a Scar on his right wrist about the size of a dime and Also a small Scar on the upper lip,” was officially freed.

Robert Harlan went west, to California, and amassed a small fortune during the Gold Rush. Some reports had him returning east with more than $90,000 in gold, while others said he’d made a quick killing through gambling. What is known is that he returned east to Cincinnati in 1850 with enough money to invest in real estate, open a photography business, and dabble quite successfully in the race horse business. He married a white woman, and although he was capable of “passing” as white himself, Robert chose to live openly as a Negro. His financial acumen in the ensuing years enabled him to join the Northern black elite, live in Europe for a time, and finally return to the United States to become one of the most important black men in his adopted home state of Ohio. In fact, John’s brother James sometimes went to Robert for financial help, and family letters show that Robert neither requested nor expected anything in return.

By 1870, Robert Harlan caught the attention of the Republican Party after he gave a rousing speech in support of the 15th Amendment, which guarantees the right to vote “regardless of race, color or previous condition of servitude.” He was elected a delegate to the Republican National Convention, and President Chester A. Arthur appointed him a special agent to the U. S. Treasury Department. He continued to work in Ohio, fighting to repeal laws that discriminated on the basis of race, and in 1886 he was elected as a state representative. By any measure, he succeeded in prohibitive circumstances.

John Harlan’s history is a little more complicated. Before the Civil War, he had been a rising star in the Whig Party and then the Know Nothings; during the war, he served with the 10th Kentucky Infantry and fought for the Union in the Western theater. But when his father died, in 1863, John was forced to resign and return home to manage the Harlan estate, which included a dozen slaves. Just weeks after his return, he was nominated to become attorney general of Kentucky. Like Robert, John became a Republican, and he was instrumental in the eventual victory of the party’s presidential candidate in 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes was quick to show his appreciation by nominating Harlan to the Supreme Court the following year. Harlan’s confirmation was slowed by his past support for discriminatory measures.

Robert and John Harlan remained in contact throughout John’s tenure on the court—1877 to 1911, years in which the justices heard many race-based cases, and time and again proved unwilling to interfere with the South’s resistance to civil rights for former slaves. But Harlan, the man who had opposed the Reconstruction Amendments, began to change his views. Time and again, such as when the Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional, Harlan was a vocal dissenter, often pounding on the desk and shaking his finger at his fellow justices in eloquent harangues.

“Have we become so inoculated with prejudice of race,” Harlan asked, when the court upheld a ban on integration in private schools in Kentucky, “that an American Government, professedly based on the principles of freedom, and charged with the protection of all citizens alike, can make distinctions between such citizens in the matter of their voluntary meeting for innocent purposes simply because of their respective races?”

His critics labeled him a “weather vane” and a “chameleon” for his about-faces in instances where he’d once argued that the federal government had no right to interfere with its citizens’ rightfully owned property, be it land or Negroes. But Harlan had an answer for his critics: “I’d rather be right than consistent.”

Wealthy and accomplished, Robert Harlan died in 1897, one year after his brother made his “Great Dissent” in Plessy v. Ferguson. The former slave lived to be 81 years old at a time when the average age expectancy for black men was 32. There were no records of correspondence between the two brothers, only confirmations from their respective children of introductions to each others’ families and acknowledgments that the two brothers had stayed in contact and had become Republican allies throughout the years. In Plessy, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Louisiana’s right to segregate public railroad cars by race, but what John Harlan wrote in his dissent reached across generations and color lines.

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is colorblind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.

In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land, has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race.

The doctrine of “separate but equal” persisted until 1954, when the court invalidated it in Brown v. Board of Education; during that half-century, Jim Crow laws blocked racial justice for generations. But John Harlan’s dissent in Plessy gave Americans hope. One of those Americans was Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer who argued Brown; he called it a “bible” and kept it nearby so he could turn to it in uncertain times. “No opinion buoyed Marshall more in his pre-Brown days,” said NAACP attorney Constance Baker Motley.”

Sources

Books: Loren P. Beth, John Marshall Harlan, the Last Whig Justice, University of Kentucky Press, 1992. Malvina Shanklin Harlan, Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854-1911, (Unpublished, 1915), Harlan Papers, University of Louisville.

Articles: Dr. A’Lelia Robinson Henry, “Perpetuating Inequality: Plessy v. Ferguson and the Dilemma of Black Access to Public and Higher Education,” Journal of Law & Education, January 1998. Goodwin Liu, “The First Justice Harlan,” California Law Review, Vol 96, 2008. Alan F. Westin, “John Marshall Harlan and the Constitutional Rights of Negroes,” Yale Law Review, Vol 66:637, 1957. Kerima M. Lewis, “Plessy v. Ferguson and Segregation,” Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2009. James W. Gordon, “Did the First Justice Harlan Have a Black Brother?” Western New England University Law Review, 159, 1993. Charles Thompson, “Plessy v. Ferguson: Harlan’s Great Dissent,” Kentucky Humanities, No. 1, 1996. Louis R. Harlan, “The Harlan Family in America: A Brief History,” http://www.harlanfamily.org/book.htm. Amelia Newcomb, “A Seminal Supreme Court Race Case Reverberates a Century Later,” Christian Science Monitor, July 9, 1996. Molly Townes O’Brien, “Justice John Marshall Harlan as Prophet: The Plessy Dissenter’s Color-Blind Constitution,” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3, Article 5, 1998

Associate Justice Joseph McKenna

Joseph McKenna in robes, C.M. Bell Studio

Joseph McKenna's Irish-Catholic immigrant parents moved their family from Philadelphia to Benicia, California, when he was twelve. Just three years later, his father died, and Joseph became the head of the family. While helping to support his family, McKenna attended parochial schools and, later, Benicia Collegiate Institute where he studied law. He passed the bar in 1865. But law held less of an allure for McKenna than politics, and, except for a brief period, he never practiced as a private lawyer. Instead, he became a staunch Republican politician.

From 1865 on, McKenna was either a candidate or an elected officeholder until he was appointed to the bench. He served in the House of Representatives from 1885 to 1892, where he displayed the knack of gaining the support of powerful figures; Leland Stanford and William McKinley both found him to be a useful ally and played a part in his political rise. Stanford suggested his name to President Benjamin Harrison for a vacancy on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1892. After McKinley became president, he named McKenna his attorney general and then, within the year, nominated him to the Supreme Court to fill the seat of Justice Stephen Field, who had finally been persuaded to retire after thirty-four years on the Court.

McKenna also would serve a long time, and his twenty-six-year tenure broke into three periods: an early period of learning his new role; a middle period when he was an important (although somewhat erratic) member of the Court; and a late period of failing abilities limiting his effectiveness. His career, especially his middle period, essentially showed him as a politician dressed in judicial robes.

At the time of McKenna's appointment, some observers complained that he was unsuited for the Court. The grumbling was politically motivated but contained a germ of truth. Nothing in his background, including his legal positions, prepared him for the Court. He was a poor lawyer and knew it, so he spent some time in the Columbia University law library to ready himself. But the cramming did little good, and a Court librarian later commented that as a new justice, McKenna was overwhelmed by the duties. McKenna's tentativeness as a justice was reflected in his writing: his early opinions—for example, Magoun v. Illinois Trust and Savings Bank (1898)—were weighed down with loads of precedent and irrelevant case law. Nor did he have a clear philosophy to guide him, and despite his long tenure, he never developed one.

Throughout his career and across many different issues, McKenna proved inconsistent in his decisions and reasoning. Typical of his lack of consistency were his votes and opinions in cases concerning state and federal regulation of working conditions. He was with the majority in Lochner v. New York (1905) when the Court struck down a New York health regulation that limited the working hours of bakers. But in the 1908 case Muller v. Oregon, he joined the unanimous majority in upholding the state's hours regulation for women industrial workers. In Wilson v. New (1917), McKenna was in the majority upholding the federal Adamson Act, which set an eight-hour day for railroad workers. A belief in dual federalism cannot explain this shift, because in Bunting v. Oregon (1917), McKenna's majority opinion sustained a state law mandating a ten-hour day that was in effect a minimum wage law. Then, in Adkins v. Children's Hospital (1923), he joined the majority in striking down federal minimum wage legislation for women in the District of Columbia, which brought him back to where he had started in Lochner.

Although McKenna never developed a consistent judicial stand, he did adapt his politician's skills to his new role. In the middle of his career, especially in the second decade of the twentieth century, his writing style returned to a more natural form, and he expressed his opinions in strong, clear phrases. His opinion in United States v. United States Steel Corporation (1920) is a brief and direct statement of the application of the rule of reason—that not all restraints of trade were unreasonable and therefore illegal—to the Sherman Antitrust Act. Moreover, his sensitive political antenna had earlier picked up the strong support for federal action under the commerce power. His opinions for the Court in Hipolite Egg Company v. United States (1911), upholding the constitutionality of the Pure Food and Drug Act, and Hoke v. United States (1913), upholding the Mann Act, reflected both his political awareness and maturing judicial powers. These two opinions are lucid and forceful statements of the federal government's power to use the commerce power to promote the general welfare. Moreover, they upheld popular laws passed in the face of supposed national emergencies.

The same pattern emerged in McKenna's votes and opinions in the free speech cases that grew out of the federal and state legislative attempts to limit expression during World War I. In a number of cases, beginning with Schenck v. United States (1919) and ending with Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920), McKenna joined with the majority in upholding these popular laws. In Gilbert, McKenna asserted that although the freedom of speech was inherent, it was not absolute. In a time of emergency, like a war, broad restrictions and limitations could be placed on speech despite the First Amendment.

The wartime speech cases were his swan song. In the 1920s he stayed on the Court even though he no longer had the ability to understand the issues. Chief Justice William Howard Taft, after McKenna's mental decline, dismissed him as a “Cubist” on the bench and several times had to ask McKenna to rework his opinions so they would reflect the accordance of the majority. His colleagues suggested he retire, but he refused. In 1924, as an expedient, the brethren—under the chief justice's direction—agreed not to make any decisions in cases in which his vote would be the deciding one. Whether it was due to the pressure of colleagues, his realization of his decline, or his wife's death, McKenna retired in 1925.

Mckenna, Joseph. (2006). In M. I. Urofsky (Ed.), Biographical encyclopedia of the Supreme Court. http://library.cqpress.com/scc/bioenc-427-18168-979380