Growing up as a young woman in Washington, D.C. in the Gilded Age was a unique experience shaped by the social norms and opportunities of the time. Education for young women was expanding, with some having access to quality schools and even higher education institutions. However, opportunities were still limited compared to today's standards, and many young women were expected to focus on domestic and social pursuits.

The capital's vibrant social scene played a significant role in the lives of these young women. They attended formal social events, balls, and gatherings, which were crucial for networking, forging connections, and potentially finding suitable marriage partners. Family and social status carried immense importance, and young women were often expected to uphold traditional values and roles. The 1890s marked a pivotal era for women's rights, and D.C. was a center for suffragist activity. Young women may have been exposed to these ideas and even inspired to get involved in the burgeoning women's suffrage movement.

Growing up in the political epicenter of the nation, young women likely encountered political discussions and activism. D.C. was a hotbed for political activity during this time, providing opportunities for engagement in political causes. Despite these opportunities, young women faced numerous challenges, including gender discrimination and limited career prospects. Societal pressures to conform to established gender roles persisted. Nevertheless, it was a time of change and transition in women's roles and rights, setting the stage for the progressive movements that would follow in the 20th century.

Miss Brooks

Miss Jackson

Mabel Dorris

Mrs. Feldman

Miss Gardiner

Mrs. F. Belford

Eleanor Danish

J. L. Ewell

Miss H. L Franklin

Mrs. C.A Flagg | Read more!

Isla Owen

Lola Small Ford

Miss Gaines

Allie Danish

Lorena Barber

Bessie Boyd

Miss Ethel Clark

Miss Mabel Scott

Miss E.B. Repp

Mrs. J.N. Pidock

Mrs. F.W. Pelly

Mrs. I.E. Harmer

Rose Holt

Miss Little

Miss Mertvago

Miss Mittie Burch

Miss Helen Wyville

Lillie White

Miss Walthour

Louise Stewart

A. Rousseau

Mrs. H. Dean

Allie Danish

May Avery

Mrs. W.F Cassman

Unidentified woman

Miss Arnett

Nellie Robinson

E.W. Neill

Mrs. D. Stewart

G.C. Sholes

Miss Salzmann

Katie Roche

R.W. Gilliam

B.M. Coon

Mrs. M.S. McElhannon

F. Matthews

Mrs. A.C. Lynn

M. Strother

Mary Leadbeter

Miss Langer

Miss Clinton

Miss M.F. Besse

Miss Coxey

Miss Rene Stephenson

Miss. V. Burke

Miss M. Van Matre

Miss. E. Roper

Miss Rosie Marsh

Miss Ella Robinson

Miss Ida Robinson

Mrs. G.T. Robinson

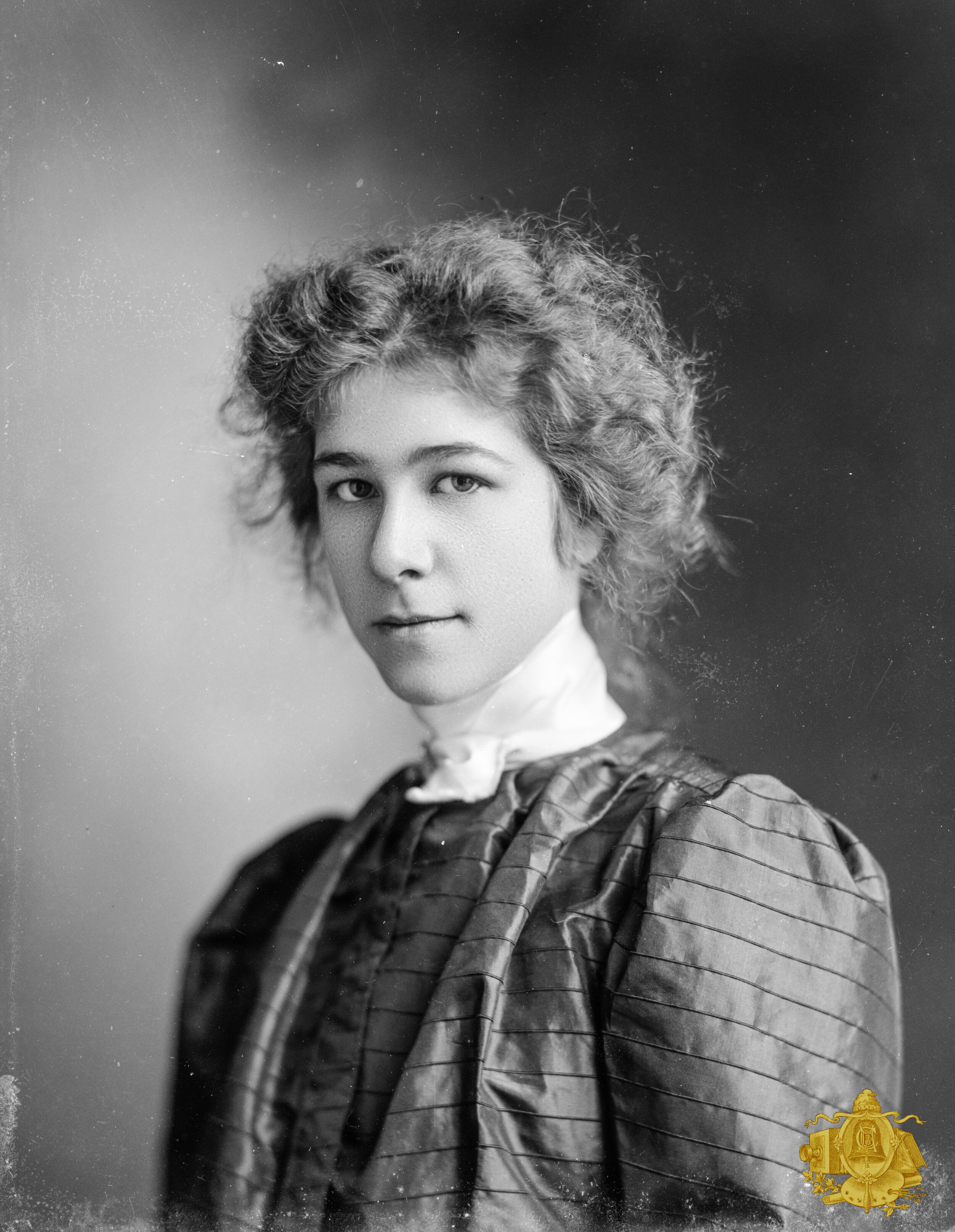

Mrs. Charles Allcott Flagg

Harriett Valentine was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1876. She was the first wife of Charles Allcott Flagg, born in Sandwich, Massachusetts, in 1870. Flagg, a librarian, authored several books narrowly concentrated on his native New England and family history. An Index of Pioneers From Massachusetts, Reference List on Connecticut Local History, Family of Asa Alcott, and The Descendants of Eleazer Flagg are still in print and available for purchase.

Harriett's photo was taken shortly after her marriage to Charles as one pose shows her hands folded to expose her wedding and engagement rings subtly. The 1894 photo would find Harriett at age 18. By 1900, Charles secured a post at the Library of Congress as an Assistant in Charge of the American history collection. Sadly, Harriett died on Sunday, April 28, 1901. She was only 24 years old. Two weeks later, on Sunday, May 12, her newborn son, George Benjamin, died. Mother and child are buried in the Old Oak Street Burial Ground Grafton, Worcester County, Massachusetts, USA.

Charles did remarry, had two children, and moved to Bangor, Maine, where he died in 1920. His son, John Benjamin, was lost at sea in 1939. His eldest daughter Anna Catherine died in 2000 at the age of 81.

Harriett D. Valentine’s headstone in Old Oak Street Burial Ground in Grafton, MA.

George Benjamin, 16 days old

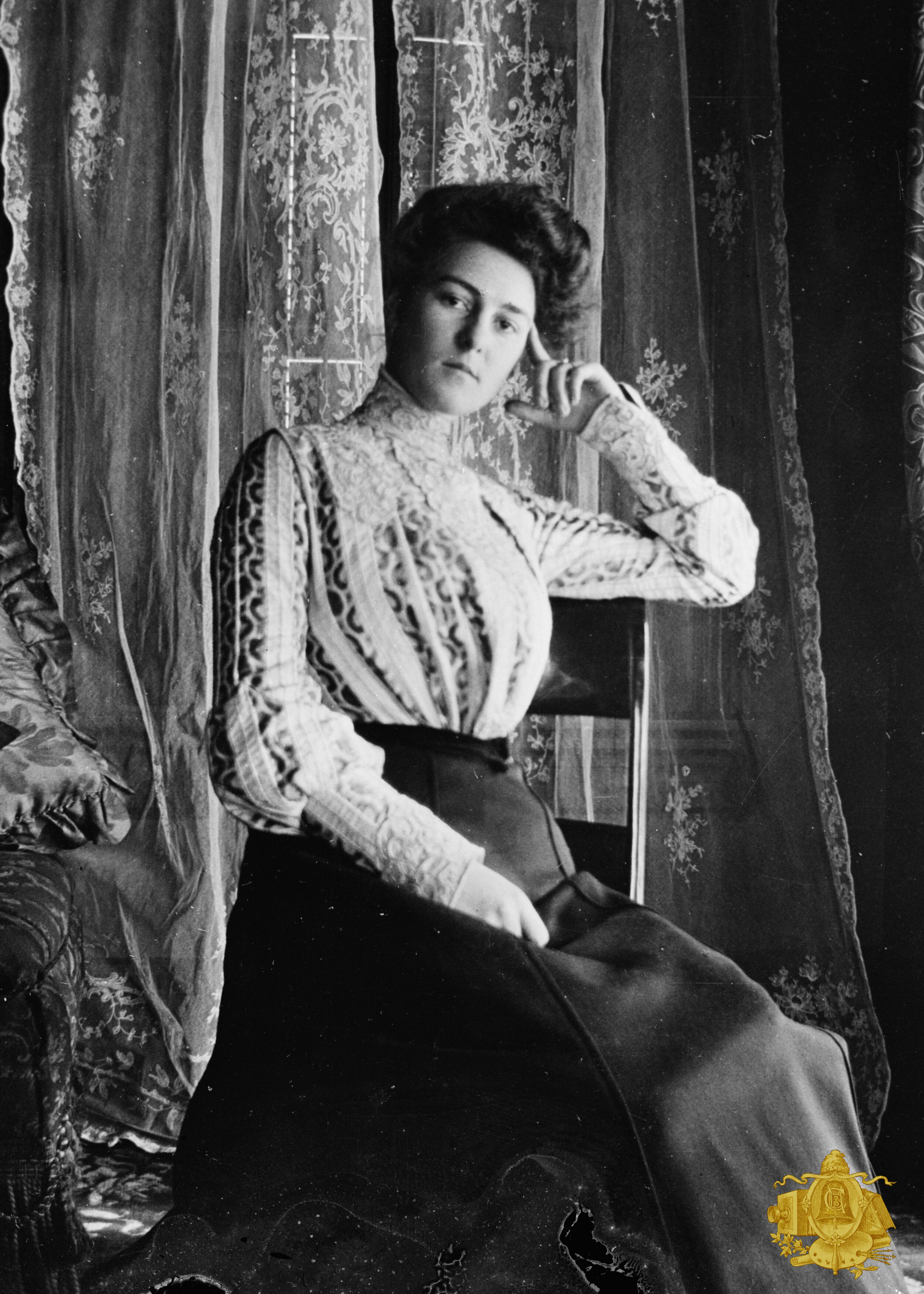

Marie de Mertvago

Marie de Mertvago, C.M. Bell Studio

Marie de Mertvago was the daughter of General Dmitrii Fedorovich Mertvago (1840-1918), the descendant of a noble family whose origins date back to fourteen centuries. From 1895 to 1899, Marie’s father held the role of naval and military attache of the Russian legation in Washington, where Marie was known as “the belle of the diplomatic corps” (Anonymous [1], 1923). In 1899 Gen. Mertvago was assigned to the war department at St. Petersburg, where Marie met Vladimir Hanenfeldt, that was to become her husband. In 1908 Zenaide was born.

As a very young child, Zenaide undertook the study of the harp and piano, and, at seven years, she was featured in Russia as the world’s youngest harpist (Anonymous [2], 1933).

Zenaide was thus on her way to a quiet and comfortable life in the high society of Tsarist Russia. But fate had decided otherwise.

In 1914 the First World War broke out, and Zenaide’s father, General Hanenfeldt, who was in charge of a regiment, died two months later, at the very beginning of the hostilities. In 1917, at the outbreak of the October Revolution, Marie and Zenaide fled Russia for Finland, where the Hanenfeldts possessed a summer home. One year later, Zenaide’s grandfather, General Mertvago, also died, and the Finnish civil war broke out. At that point, Zenaide’s mother, seeing the rapid deterioration of the situation and thinking about the safety of her young daughter, decided to return to the United States, where she could still count on many friends. Thanks to the financial support of some of these American friends, the two arrived in New York in January 1919, when it was nearly impossible to get permission to come over.

At this point, Mary, in exile and impoverished, and despite not having worked a single day of her life, had to face the problem of supporting herself and little Zenaide. It was the beginning of an odyssey that led her to change jobs and places of residence many times: teacher of French and music in a girl’s school in New Jersey; nursery governess for a wealthy American family in Florida; music teacher in the Unquowa School in Bridgeport, Conn. (Anonymous [3], 1920); book agent for a Philadelphia firm publishing a pseudo-medical book (Anonymous [4], 1923). At the same time, Mary worked for the community of Russian exiles in the United States, under the umbrella of the American Central Committee for the Russian Relief, by organizing concerts of Russian music (Anonymous [5], 1920) and giving lectures on the conditions of Russia under the Bolshevik regime (Anonymous [3], 1920). In 1923, while temporarily leaving Zenaide in Torresdale, near Philadelphia, where the little girl was attending school, Mary returned to Washington, determined to take advantage of the contacts in the diplomatic corps cultivated at the time of her first stay in the capital. At first, she taught Russian cooking to the wives of Washington diplomats (Anonymous [1]). Then, besides teaching piano and the Russian language, Mary became a frequent lecturer on Russian culture, giving lecture-recitals on Russian music, where she also played piano and Russian theatre. Mary even appeared on WRC radio as a pianist. In the end, Mary and Zenaide settled in Washington and, in 1927, they obtained U.S. citizenship (Anonymous [6], 1924).

Zenaide Hanenfeldt: The Scion of Imperial Russia That Became a Theremin Diva | By Valerio Saggini