Edward Sheriff Curtis

As Charles Milton Bell refined his portrait work within the walls of his Washington, D.C., studio in 1885, another vision of photography was taking shape thousands of miles away. On the wide, untamed landscapes of the American West, Edward Sheriff Curtis was emerging as one of the most influential documentarians of Native American life. While Bell’s work often depended on dignitaries, leaders, and delegations visiting the capital, Curtis immersed himself in the field, traveling across plains, deserts, and mountains to meet his subjects where they lived.

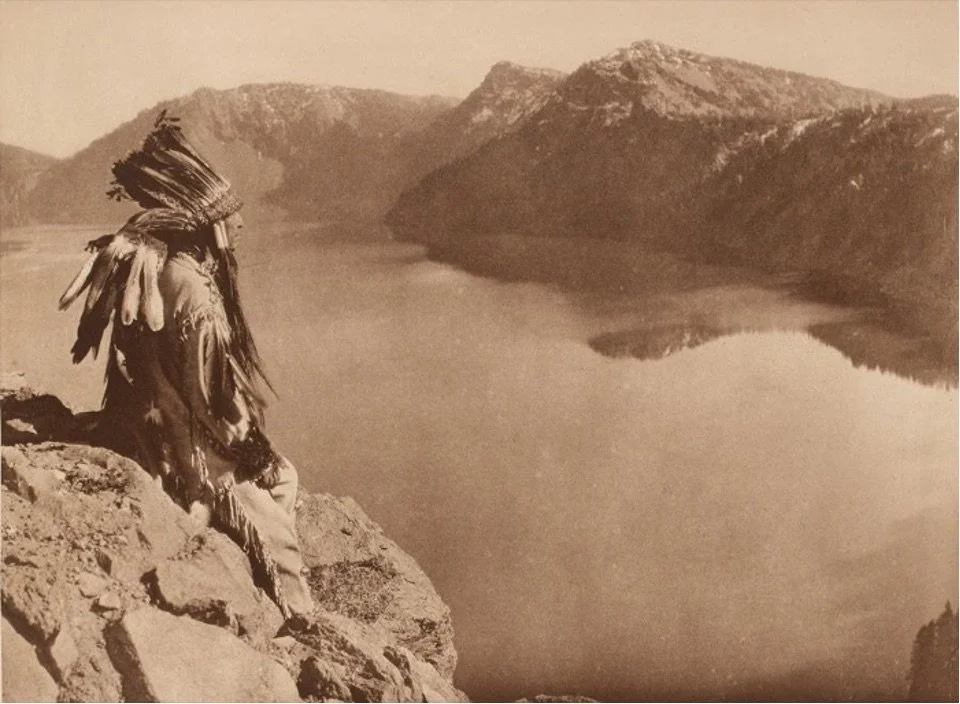

Curtis held a deep conviction that he was witnessing the final generation of traditional Native life before it was erased by federal policies, westward expansion, and cultural assimilation. His mission, as he declared, was to honor “the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind” and to preserve its memory “at once or the opportunity will be lost.” With this sense of urgency, he not only captured thousands of photographs but also became one of the first to expand the scope of ethnographic record-keeping into new technologies. By 1906, he was recording songs, languages, and oral traditions on wax cylinders and producing some of the earliest moving pictures of Native communities.

Curtis’s work, monumental in both scale and ambition, stands as a counterpart to Bell’s studio portraits. Together, they illustrate two distinct but equally important approaches to 19th-century photography: one centered in the carefully composed space of a studio, the other unfolding across the vast canvas of the American frontier.